Culture

Why Charli XCX might be gen Z’s answer to the Romantic poets

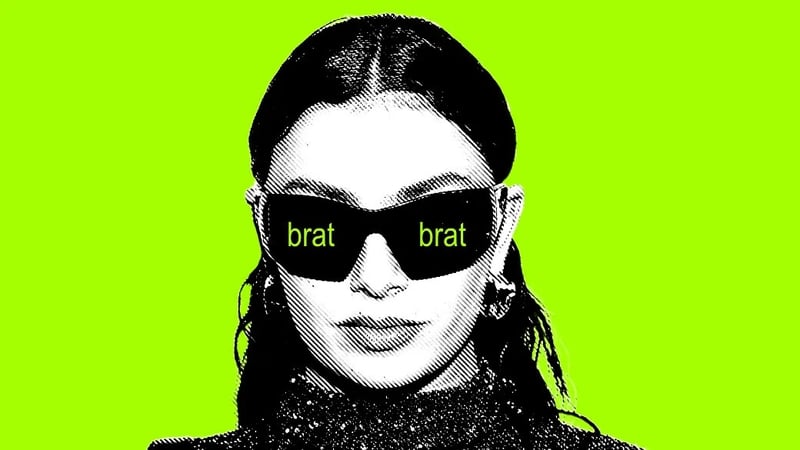

Popstar Charli XCX is turning her hand to acting in the new film Erupcja. In it, she recites Lord Byron’s poem Darkness. Charli and Byron may be 200 years apart, but the legacies of Romantic poetry are alive in Brat, the singer’s sixth studio album, writes Katie MacLean.

Byron has often been described as the first modern celebrity, notorious in regency England for rumours of incest, homosexuality and vampirism. Irish writer Marguerite Gardiner, Countess of Blessington, wrote in 1823 that “Byron had so unquenchable a thirst for celebrity, that no means were left untried that might attain it.”

Brat is similarly concerned with the self-construction of identity and celebrity in Charli’s “party girl” image. Her interest in fame is reflected both in her album’s extensive branding and in lyrics like, “When I go to the club I wanna hear those club classics/I wanna dance to me”.

(Pic: Getty)

In Might say Something Stupid, Charli admits that she is “famous but not quite” and doesn’t know if she “belong[s] here anymore”. This echoes John Keats’ 1818 poem When I have fears that I may cease to be, in which he laments that he might die before he experiences true literary achievement and fame. Charli has inherited the identity of lonely artist obsessed with creative genius from the Romantics.

Anxieties around legacy resurface in Apple. Charli uses the apple as a Gothic metaphor for inheritance and cursed fate, not unlike Byron’s On Leaving Newstead Abbey, in which he imagines his ancestors haunting him until death. Romantic poetry is full of this tension between inheritance and decay, and Charli’s lyrics show how those anxieties still haunt us today.

We need your consent to load this Spotify contentWe use Spotify to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

Romantic poets were obsessed with the archaic and classical through Greek and Roman mythology, ruins, and medievalism, like John Keats’ poem Ode to a Grecian Urn. Similarly, Brat frequently looks back with references to Y2K aesthetics and early 2000s culture.

Charli romanticises nostalgia in the song Rewind:

Used to burn CDs full of songs I didn’t know

Used to sit in my bedroom, puttin’ polish on my toe

Recently, I’ve been thinkin’ ’bout a way simpler time

Sometimes, I really think it would be cool to rewind.

In both cases, romantic nostalgia becomes a creative lens to explore our relationship with the past.

Romantic poets were fascinated by the sublime, characterised as the overwhelming power of nature. In Wordsworth’s Lines Composed A Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey, he contrasts “the din/Of towns and cities” against awe-inspiring “steep and lofty cliffs”.

In the song, Everything is Romantic, Charli instead finds beauty in juxtaposing symbols: the man-made (“Bad tattoos on leather tan skin/Jesus Christ on a Plastic sign”) contrasts nature (“Lemons on thе trees and on the ground/[…] Pompeii in the distance”). Where the Romantics rejected the artificial, Charli embraces it, extending Romantic ideas into the 21st century.

The most explicitly romantic song on Brat is So I, an elegy for the producer Sophie, who died suddenly in 2020. Just as in romantic elegies, Charli laments the loss of genius: “Your star burns so bright/ […] You had a power like a lightnin’ strike”.

Percy Shelley’s elegy Adonais, written on the death of Keats, concludes that the genius of Keats lives on through his poetry. Similarly, Charli sings: “Your sounds, your words live on, endless.” The influence of Romantic elegies can still be seen in popular culture through music, particularly songs which immortalise fellow artists and explore contemporary understandings of grief.

The media studies academic David Tetzlaff argues that, “Romanticism remains the common language of middle-class rebelliousness.” Brat rebels most obviously in its neon green branding, hyperpop tracks and aggressive autotune, becoming one of Rolling Stone’s250 greatest albums of the 21st century so far. So, Brat Summer’ may been a neon green Tik-Tok trend, but the album perfectly showcases how Romanticism influences art and culture today.

As Matt Sangster, an expert in 18th-century literature and material culture, writes in David Bowie and the Legacies of Romanticism, “[t]he ways that texts happened in the past are hugely important, but texts and the idea clusters they spawn are also fascinating for the complex ways that they continue to happen in our lives.” Concerns inherited from the Romantics are evident in Brat, with its exploration of celebrity, nostalgia, nature, legacy and loss. Romanticism isn’t stuck in the 19th century – it is alive today in the very places you may least expect.

Katie MacLean is a PhD Student at the University of Stirling. This article originally appeared in The Conversation.