This is an awful thing to say, but I wonder what society would be like if there was a drug you could give teenagers to stop them being homosexual

— O’Reilly on societal attitudes to deafness

Culture

‘This was not the way my parents grew up. People were not proud of their deaf children’

Read more on post.

In the first few weeks of life a baby has a hearing test. If the baby is deaf “the doctors will say your child has failed the hearing test. The word ‘failure’ is associated with the birth of their deaf identity,” says Shane O’Reilly. “They have failed something in becoming who they are.”

The writer is talking about “a magical thing” that Rhiannon May said on the first day of rehearsals for Her Father’s Voice, O’Reilly’s new play. As the English actor, who is deaf, and O’Reilly, a Coda, or child of deaf adults, put it, the way such news is communicated is “the difference between seeing deafness as a culture and identity, a wholeness, or seeing it as a deficiency, a lack, a disability”.

Considering cochlear implants can pose philosophical dilemmas. It’s also meaty territory for what’s shaping up to be a big, ambitious show, with big, ambitious ideas, as well as family dramas, at Dublin Theatre Festival.

Her Father’s Voice has been seven years in the making. What started as a two-hander set in an attic is now a large play with “a far more nuanced and complicated perspective”, and with an opera and film implanted within it.

Nineteen people – actors, opera singers, musicians and the Grammy-nominated conductor Elaine Kelly – will be on stage. “It’s a complicated construction to hopefully create something very simple,” says O’Reilly, who is tweaking the script before it is printed.

A hearing couple, he a contemporary opera composer, she retraining as a doctor, and their deaf six-year old daughter, Sarah, move back in with her parents. Amid the tensions of three generations under one roof, the younger couple wrestle with the weight of their decision for Sarah to have cochlear-implant surgery. The unexpected arrival of a deaf mother and daughter unearths buried ghosts of previous deafness in the family.

As surgery looms, it morphs into the father’s opera, based on film of Sarah’s birthday party at a swimming pool. The film shoot involved “12 little girls, 47 people on set. It was wild and also unbelievably dynamic. There are deaf people, there are hearing people. Children with cochlear implants. Children who are deaf who don’t have them.

“This absolute mix, and film crews, lighting teams, a body of water. Multiple languages” – including Irish Sign Language and British Sign Language – “and people who can and cannot access the vocal score, which has to be matched with the music in the opera. It was one of those days where everyone just leaned in, and it was magic.”

[ John Cradden: We deaf people have been making ourselves heard … loudlyOpens in new window ]

The 25-minute contemporary opera, by Tom Lane, is “a sweeping journey towards the final scene in the audiologist’s office. In the final moments the girl is switched on, and we start to hear what she hears,” the music through her cochlear implants, using technology they’ve developed to filter the playing and singing. The two young actors alternating as Sarah were born deaf and have cochlear implants.

“This is not a polemic,” says O’Reilly. “I’m not making an argument for or against anything. It’s an exploration of people trying to do what they think is best. I think people are always trying to do what’s right. But we don’t live in a world where everyone agrees what right is.”

This is all very personal to the playwright. “Growing up in a deaf household, I didn’t know we were lacking anything, because everything was there. Language, culture, identity, a sense of comfort in ‘This is who we are.’”

He describes growing up surrounded by aunts and uncles and neighbours in Churchtown, in Dublin. The house was busy and noisy, and he and his sister, Aoife, were noisy kids. Deaf people would show up unannounced (phone calls being impossible).

“And suddenly there’s 10 deaf people, and a ferocious evening of catch-up and chat. People think deaf households are quiet. Deaf people are very vocal.”

The old term “deaf and dumb” is very insulting, says O’Reilly. “It insinuates these people do not speak, whereas everybody is attempting to engage with the generation of sound and speech. When I’m at home now, my mum says something across the kitchen. I understand exactly what she’s saying. And now my husband understands.” His husband is Paul Curley, an actor. “We chat away. She’s always roaring and screaming at him, and he’s laughing his head off.”

O’Reilly’s mother, Susan, was born profoundly deaf. His father, Bernard (or Waffo), lost his hearing to meningitis, “so has some access to the world of sound” and wears hearing aids. She’s a special-needs assistant at Holy Family School for the Deaf, in Cabra in Dublin. He’s a carpenter on Francis Street, the city’s antiques quarter.

O’Reilly recalls friends meeting his deaf parents when they were younger. “Some people were very uncomfortable, just wanting the interaction to be over.” Sometimes it was like “a lack of respect for a parent. I was raised that if you go to your friend’s house, you say ‘Hello’ and ‘Thanks for having me’. That was not always afforded to my mum and dad.

“But one of my best pals from college – he’s from London – I could have cried. Straight in: ‘All right, then, Mrs O’Reilly!’ We’re going to make this work. Kept going. He didn’t care that it was uncomfortable. He’d learned that discomfort is an opportunity.”

This seems key to O’Reilly’s connections within and without the family.

“I spent so much of my childhood interpreting everything and feeling I must make everything okay, make sure everybody’s understood and that nobody’s offending anybody.” When friends lean in, “I have this immediate sense of calm.”

The deaf community getting together, “like immigrants here, or the Irish abroad”, have “that sense of, ‘We’re together, and we know each other intimately.’ We had that going to the deaf club in Cabra. Mum chatting away to all her pals. I can sign with the deaf kids.

“We were always included, as the hearing kids of deaf parents. And we’re all flying around, the deaf and the hearing kids all together. We had a football team, half-deaf, half-hearing.” That openness taught him a lot subconsciously, as a child.

He’s aware of his parents’ generation spending their lives in a system, in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, “where Ireland was very hostile towards deaf people. Those schools were not easy places to be and had a dark history. They’ve come through that, and they’ve pushed into the workforce. They’re making lives, they’ve bought homes, they’re raising children.”

When cochlear implants first became available, many deaf people regarded “this announcement, with celebration, that their deaf children can be made into hearing children” as a rejection of their culture. Doctors were threatened. “The deaf community felt like this was an attack.”

“Now we have an empowered deaf culture, where sign language comes first, and a lot of the deaf community’s relationship to cochlear implants is, ‘Absolutely get a cochlear implant, but don’t stop signing, and do not take the child out of the deaf culture. Continue to give them access to everything.’”

O’Reilly understands a hearing person with a deaf child wanting their child to access and engage with the world the same way they do. But if the child already has access to an empowered culture, “then the dilemma becomes deciding between two things, as opposed to a problem and a solution”.

He talks about the drive to cure, to improve. “This is an awful thing to say, but I wonder what society would be like if there was a drug you could give teenagers to stop them being homosexual”, which was long considered dysfunctional.

Early in the research, he and Lane, the composer, spent time with the cochlear-implant and audiology team at Beaumont Hospital. “They’re so passionate about this as a positive thing, as an opportunity to help children access something.”

They explained how the human brain starts a relationship with a piece of technology, and how it’s different for everyone. “This is about your brain chemistry.” The “unknownness of it” interested O’Reilly. “Fundamentally, we don’t know whether it will work for your child or it won’t, whether emotionally, in the future, they will feel happy with this decision” their parents made.

A line in the play comes from doctors describing the little hairs inside the cochlea transmitting sound, which is how we hear. Even deaf people have some functioning hairs. Before surgery, they’re destroyed. “The doctor described it as driving a JCB through a daisy field.”

If he had a deaf child would O’Reilly opt for surgery? “I have no idea.” He’s not deflecting. He observes how everything changes when a baby is born. “Priorities are immediately stacked in a different order.”

He has “very proud deaf friends” who’ve chosen implants for their children, to give them options. He’s also aware some people’s experience is not good, and some later regret their parents’ decisions.

“Not everything I make is about the deaf community,” says O’Reilly, but he does keep coming back. He wrote and performed in Follow, with WillFredd Theatre Company, in 2011, “performing in sign and speech, so my parents and their friends could see something I was in” without having to look right, off the stage.

He wrote Window Pane for the Abbey Theatre’s Dear Ireland project, with Amanda Coogan performing behind a pane of glass, and the short film Pal, with a deaf cast. “I’ve written a lot of work representative of the deaf perspective, coming at the world from that lens I grew up with.”

Today is O’Reilly’s last in rehearsals. “It feels the stakes are high. I feel very protective of that world, of the narrative around it, of my parents, that community.”

For his parents, “I think it makes them proud. Because this was not the way they grew up. People were not proud of their deaf children. People were not proud of the noises deaf people made, of the spectacle of sign language. So for their son to repeatedly and endlessly talk about it, I hope for them there’s a catharsis.”

Her Father’s Voice, which is running as part of Dublin Theatre Festival, previews at Draíocht, Blanchardstown, on Saturday, September 27th, and at O’Reilly Theatre, Dublin, on Wednesday, October 1st. It is then at O’Reilly Theatre from Thursday, October 2nd, to Sunday, October 5th

Culture

Giorgio Armani creations interplay with Italian masterpieces at new Milan exhibition

Read more on post.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Giorgio Armani, Milano, for love’’ at the Brera Art Gallery opens today, mere weeks after the celebrated designer’s death at the age of 91.

Featuring 129 Armani looks from the 1980s through the present day, the exhibition places his creations among celebrated Italian masterpieces by such luminaries as Raphael and Caravaggio.

It is one of a series of Milan Fashion Week events that were planned before Armani’s death, to highlight his transformative influence on the world of fashion.

“From the start, Armani showed absolute rigor but also humility not common to great fashion figures,’’ said the gallery’s director Angelo Crespi. “He always said that he did not want to enter into close dialogue with great masterpieces, like Raphael, Mantegna, Caravaggio and Piero della Francesca.’’

Instead, the exhibition aims to create a symbiosis with the artworks, with the chosen looks reflecting the mood of each room without interrupting the flow of the museum experience – much the way Armani always intended his apparel to enhance and never overwhelm the individual.

A long blue asymmetrical skirt and bodysuit ensemble worn by Juliette Binoche at Cannes in 2016 neatly reflects the blue in Giovanni Bellini’s 1510 portrait “Madonna and Child”; a trio of underlit dresses glow on a wall opposite Raphael’s “The Marriage of the Virgin”; the famed soft-shouldered suit worn by Richard Gere in American Gigolo, arguably the garment that launched Armani to global fame, is set among detached frescoes by Donato Bramante. Every choice in the exhibition underscores the timelessness of Armani’s fashion.

Armani himself makes a cameo, on a t-shirt in the final room, opposite the Brera’s emblematic painting “Il Bacio” by Francesco Hayez.

“When I walk around, I think he would be super proud,’’ said Anoushka Borghesi, Armani’s global communications director.

Armani’s fashion house confirmed a series of events this week that Armani himself had planned to celebrate his 50th anniversary. They include the announcement of an initiative to support education for children in six Southeast Asian, African and South American countries. The project, in conjunction with the Catholic charity Caritas, is named “Mariu’,’’ an affectionate nickname for Armani’s mother.

In a final farewell, the last Giorgio Armani collection signed by the designer will be shown in the Brera Gallery on Sunday, among looks he personally chose to represent his 50-year legacy.

“Giorgio Armani – 50 Years” opened to the public today at the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, Italy. The exhibition lasts until 11 January 2026.

Culture

The last day of doomsday: What is the viral ‘RaptureTok’ trend?

Read more on post.

ADVERTISEMENT

If you’re reading this today, Wednesday 24 September 2025 could be the last day before the end of the world as you know it.

If you’re reading this tomorrow, you weren’t blipped out of existence and good luck with all the rebuilding. Please do better.

Confused? We’ve got you covered.

According to the more holy corners of TikTok, it has been prophesized that yesterday – or today, they couldn’t make their minds up on which one, so just go with it – is the day of the Rapture.

For the filthy heathens among you, that’s the long-awaited end-time event when Jesus Christ returns to Earth, resurrects all dead Christian disciples and brings all believers “to meet the Lord in the air.”

It wasn’t yesterday, clearly, so today’s the day… And turn off that R.E.M. song, this is serious.

This all stems from South African pastor Joshua Mhlakela, who claimed that the Rapture will occur on 23 or 24 September 2025. Mhlakela said that this knowledge came directly from a dream he had in 2018, in which Jesus appeared to him. Mhlakela reiterated all of this on 9 September in an interview with CettwinzTV and since then, the prophecy has become a viral sensation on TikTok.

Many individuals on the social media platform have taken this literally and very seriously, with more than 350,000 videos appearing under the hashtag #rapturenow – leading to the trend / popular subsection dubbed ‘RaptureTok’.

Some videos mock the prophecy, but you don’t have to scroll for too long to find those who are completely convinced that it’s happening today.

There’s advice on how to prepare; tips on what to remove from your house should certain objects contain “demonic energy”; and testimonies of people selling their possessions. One man, who goes by the name Tilahun on TikTok, shared a video last month, in which he said he was selling his car in preparation for the big day. “Car is gone just like the Brides of Christ will be in September,” he said.

One woman in North Carolina was live recording yesterday from the Blue Ridge Mountains, fervently keeping an eye on any holy activity in the sky. Another claimed that her 3-year-old started speaking in Hebrew, thereby confirming that it’s all legit.

Some more distressing videos include American evangelicals saying goodbye to their children for the last time… We won’t share those, as they’re actually quite depressing.

It’s hard to completely blame TikTok users for wanting the final curtain to drop, as things aren’t going too great down here on Earth. That being said, it’s worth noting that the Bible never actually mentions the Rapture; it’s a relatively recent doctrine that originates from the early 1800s, one which has gained traction among fundamentalist theologians – specifically in the US, where everything is fine, civil conversation is alive and well, no one’s worried, and they’re all enjoying their “God-given freedoms”.

So, if the Rapture does come to pass, we here at Euronews Culture will be eating a whole concrete mixer full of humble pie. If it doesn’t, see you tomorrow, and do spare a thought for those who are going to be very disappointed on Thursday 25 September.

And if extra-terrestrial beings followed Tara Rule’s advice (see below), thank you alien visitors for joining in on the fun. And if you could provide some much-needed guidance on how to do better, that would be grand.

Only a few more hours left to find out…

Culture

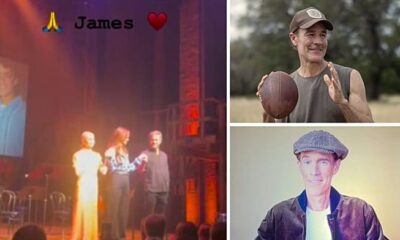

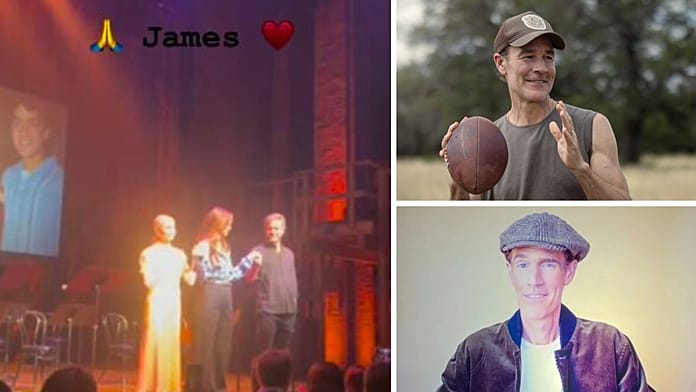

‘Dawson’s Creek’ reunion sees James Van Der Beek make surprise appearance amid cancer battle

Read more on post.

>~)JՍZ}”JsjM9DmlUEbNZkqc#ӺƏ9.ܔdܛnJǷoMv

-2j9m6Q:n4^N`/9kn^

F.0XUXA8XAojLg*z8

Z1aMXY}3*|&+=MFWkشz`Tba֑9!zWW.S`HXYkRy=@2�`’bClPz^L$V�+MsB0=uMcOݩʃ??x9 Ӝs4Ы֙?r>v.:3iT;>tDvq>t)2K“b96z3M7Ҿ6Ǯ�.Q�8&уlQx˛yly珬ſ’)m3CȅZHƘ!B|!},c8>t/kHY,w=ŷ¸W۶(;HxGc(j

ŒqƣTFH!dXV]Xr!$gz_U ?|>Z@*] I756RTj`p’ߕ$v&yk0#Mp’%!C}}XE

+w!s|Mrk2°DuA- +vC#9�0V2}ldĒ� 5‚Pj~,r6gT+鵽xPikKH#Ρ|y/P~I8M*|܅!%%畫^@”;݈7ԅDA+b_|ܾJ.): !

OyZRlj2aE`6k5nTn0HCe@BytRl:(Kf7lˊ9̦CCp%pip OnnLKzl:;7ڀ;

Ű@[̍RI$l@}..04 ́7!0 Fckט..&8wu”iml1:9_s/RvB-vz@pAnհ ?kjAM]b�ʆݙeް dPS(XC֡[Oc8m}`:_f9h2aW0T8>|DÚTʔG$%M’ވ x5Fb-,ϒ0-xNJĂѡR4 0IY+DɳL+٩9>`kibM@QiXZ6h?˶W݀lylfn}=Z0Z)[ީPܦ}ѯ2

47mJJeBsHSW}[Bx�UoaăY&oAl-“.bhIm7í[!8N$giN;^rn_Ĕ}³S2مц4߰oqdtDJMF Go3�W�!u(cq=GR|?FqԈIv1]L#9

b)th twu?/5kKx;{!~$a@_YRkѶzGTI|G/wֈ?4F2[,$$B#YЦ(>הO-J2@q]pܽw+00U%:=Gp+%M`I;tRw}1»

3jW#ѓ!OҖLi”?ƞC!~hb?RWaSJj{nfBn0KdQ-2bBThZKC4=

2[=Dɧ8څH[sr(|c2v�Wpw>Meh;= VrDž>4zfߥi@cR9Od>,k[‘.#5-6!eRNq[K`jTBN5Bl

0486Kl&s̟YX烿6z8![NkiؓmFJg99:N”8IFE$H͂vA|1v-q.Am,O~xB;:z鐵Zn=?gNEDf(“xl,KtK0|o5.׀-bSñD{6�P*&T3w}`vHGdCTrzڝ:j{tM} 9

oެ.NpO#̌6;Ywz,KLo6$ :nL!2)}qI&.&Jh

5-+.z[

I!v-1By$Sۋ; ;n~ҍBLbE/ˏs,YN5D~Rh$I;9⣹f�

h~4FN&2wzA.n”&c!Fqf{0=O”R| PuԽUGR5){p4y#h2gn]ojIxn]SZsǝ ]__܇02?ccjɥ

c6N:亂cc *8V?b;#)Wpї!L,>PUmgm,

Un^}X

9g.rjKGΜ>cA;PnrY՞>zw3^_haIH=O]5N7H@u_3i6k{F3}wq>Bػ`L**I:UH*wf&ĔB

&Z:Xw1j?RdXhn9zŔ1LB#Z`֣n6^yp!O

jAT^NϞË)6& x- oދ!

҄wu/m0wǕ”2+s&wv?UVcm>(nbyS(4 t4ԎrGs@!QՐ5X62}ə5-xC챛MB@’c?Mz2,muF!Q2v9Ngr,{]y%FMktV{;:eDHig0FŹH@

gZ6D}6m{3+^X0 8J%vYpoܳPc1PcSHarj,Sٛ8w`Ψ:#uN4 U=m0{f:6L ѳ IᱭsuSSdɽRYNA9*?lHw

gfDwI A

c|*b�ՋN%OweN9=|l01″#.s .�dv9k)%!-2bY#E)ʈ`STģ (%2 *3

RMT7֏dd_ oTWhZb$p##EϚ> ‘Q^*o5 ,3^uA

“(i5VeVPXAIH.di#7″Y1~>=T6kb[&DXoKA480c6=X·m6Ƶ%y ̫}]f@�&@sr* MX$Wx

!LkZ�'[l9,=J!4PwQuNlmSivp,]eF!#|$V`0^(=̅(Re6+#8odd0ۙMY`-Dnʫ1%Rc>5N[ǥ%*l寓M>w ;L|WB�Q] )8’ϧ _G[E2/֢ܽ#` M#M4-‘Oan’-2#t|vb=W

PzNF`?K>b=)?V[>lhtj`x-.OFԊ2GCEusq ‘ʬ#d+ɍa0

яiЇ^>”[�e�pl/0D,d8 Z۠bny螜+57d�C[/2$%+~)qH^ۈyڌ z]Pkw:+DP; d08p*5-)M

,Ѹf[‘w9)ƊE#%fqfڠY!#dV

%Zx ;z!V?RB”/i멝V)M4+wN’Jl:dlU$W:’;YU1.d1oW]1SEpӚ=зNvӿqDPEU jOjJ͈e^ z|j~8UJ1S8fZ#rh+/crq%Mo?apyhfKCۅbsʛtɽF̭*p 3M;?H쯶oPݸڨa;Ē8$TVxإ=Z*6Oݾ

-

Culture2 days ago

Taylor Swift’s new cinema outing generates more than €12million in just 24 hours

-

Politics2 days ago

European Parliament snubs Orbán with vote to shield Italian MEP from Hungarian arrest

-

Culture1 day ago

Milan Fashion Week 2025: Unmissable shows and Giorgio Armani in mind

-

Business13 hours ago

Households to be offered energy bill changes, but unlikely to lead to savings

-

Opinion2 days ago

AI Is Pointless If It Doesn’t Boost Productivity

-

Culture2 days ago

Marvel stars Mark Ruffalo and Pedro Pascal stand up for Jimmy Kimmel as Disney boycott intensifies

-

Culture1 day ago

Traitors Ireland finale: A tense and thrilling conclusion to a spectacular first season

-

Culture2 days ago

From Koniaków to Paris: how traditional Polish crocheting is captivating high fashion