Opinion

Not all diabetes is about sugar – understanding diabetes insipidus

Read more on post.

Diabetes mellitus – known to many as type 1 and type 2 diabetes – gets all the attention with its rising global prevalence and connection to lifestyle and autoimmunity. Meanwhile, its lesser-known relative – diabetes insipidus – more quietly affects hundreds of thousands of people worldwide, but is an altogether different condition, unrelated to blood sugar.

Both forms share the same defining symptom: excessive urination. The word diabetes comes from ancient Greek meaning “passing through”, which perfectly captures what happens to newly affected patients.

In the more-familiar diabetes mellitus, sugar builds up in the blood because the body either doesn’t make enough insulin or can’t use it properly. When this happens, extra sugar enters the urine, and that sugar pulls water out of the body along with it.

People with diabetes may notice that they need to urinate more often and in larger amounts than usual. Sometimes, the urine can even have a sweet smell. Legend has it that Hippocrates, the “father of medicine”, used to taste his patients’ urine to make the diagnosis. Thankfully, we now use dipstick tests instead.

Diabetes insipidus is very different from diabetes mellitus. It has nothing to do with blood sugar. Instead, the problem is with a hormone called arginine vasopressin (AVP), also known as anti-diuretic hormone (ADH), which normally helps the body control how much water it keeps or loses.

This chemical messenger, produced by the pituitary gland at the base of your skull, acts like your body’s water conservation system. When you need to hold on to fluid – say, when you’re dehydrated – AVP tells your kidneys to reabsorb water rather than letting it escape in urine.

When this system breaks down, the results are dramatic. Without enough AVP, or when the hormone fails to function properly, your kidneys lose their ability to conserve water. No matter how much you drink, you remain perpetually thirsty and dehydrated, producing large volumes of pale, diluted urine. It’s a frustrating cycle that affects around 2,000 to 3,000 people in the UK alone.

The most common culprit is AVP-deficiency (formerly called central diabetes insipidus), where the problem lies in AVP production itself. It’s actually made in a brain region called the hypothalamus before being transported to the pituitary gland, from where it is released.

Brain tumours can damage this delicate system, as can head injuries or brain surgery. Genetics sometimes plays a role, and neurological infections like syphilis or tuberculosis can also disrupt hormone production. In some cases, however, doctors are unable to identify a clear cause.

Pregnancy brings its own unique version called gestational diabetes insipidus. The growing placenta produces an enzyme that breaks down AVP in the bloodstream before it can do its job. Fortunately, this rare condition typically resolves after birth.

For AVP-deficiency, treatment is more straightforward. Patients can take desmopressin, a synthetic version of AVP available as tablets, injections, or even a nasal spray. This replacement therapy effectively restores the body’s ability to conserve water.

Things get trickier with AVP-resistance (formerly called nephrogenic diabetes insipidus), where the kidneys themselves fail to respond to AVP.

Sometimes present from birth, this form can also develop later due to kidney damage from electrolyte imbalances or certain medications. Lithium, commonly used to treat bipolar disorder, is one such example. Since the problem is the kidneys’ inability to respond to AVP, different medications are used. Low-salt diets and careful attention to staying hydrated are also key.

When thirst goes wrong

Perhaps most puzzling is dipsogenic diabetes insipidus, where the brain’s thirst centre goes haywire.

Also located in the hypothalamus, this control centre can be damaged by tumours, trauma, or infections, leading to an insatiable urge to drink water. The excessive fluid intake then suppresses AVP production, creating a vicious cycle. Dangerously, it can dilute blood sodium levels, causing headaches, confusion and even seizures.

The symptoms of this condition sometimes overlap with psychogenic polydipsia, where mental health disorders – particularly schizophrenia – drive compulsive water drinking. The consequences can be severe, as seen in one documented case where a young patient suffered complications after consuming an astounding 15 litres of water per day.

These extreme examples of pathological water intake stand alongside wellness trends promoting excessive hydration as part of a healthy lifestyle. NFL quarterback Tom Brady has famously recommended drinking around two gallons daily – nearly eight litres.

Steve Jacobson / Shutterstock.com

While we’re often told to drink more water to avert dehydration, constipation, kidney stones and the like, there’s clearly a dangerous level. Sustained or unexplained high water consumption is not only toxic to the body but may be a sign of an underlying health problem.

Diabetes insipidus reminds us that the term “diabetes” encompasses more than blood sugar problems. This other diabetes may be less common, but for those affected, the consequences of leaving the condition untreated may prove severe. Anyone experiencing persistent excessive thirst, water consumption, and urination should seek medical attention promptly. The cause may turn out to be sugar, hormones, or something else entirely.

Opinion

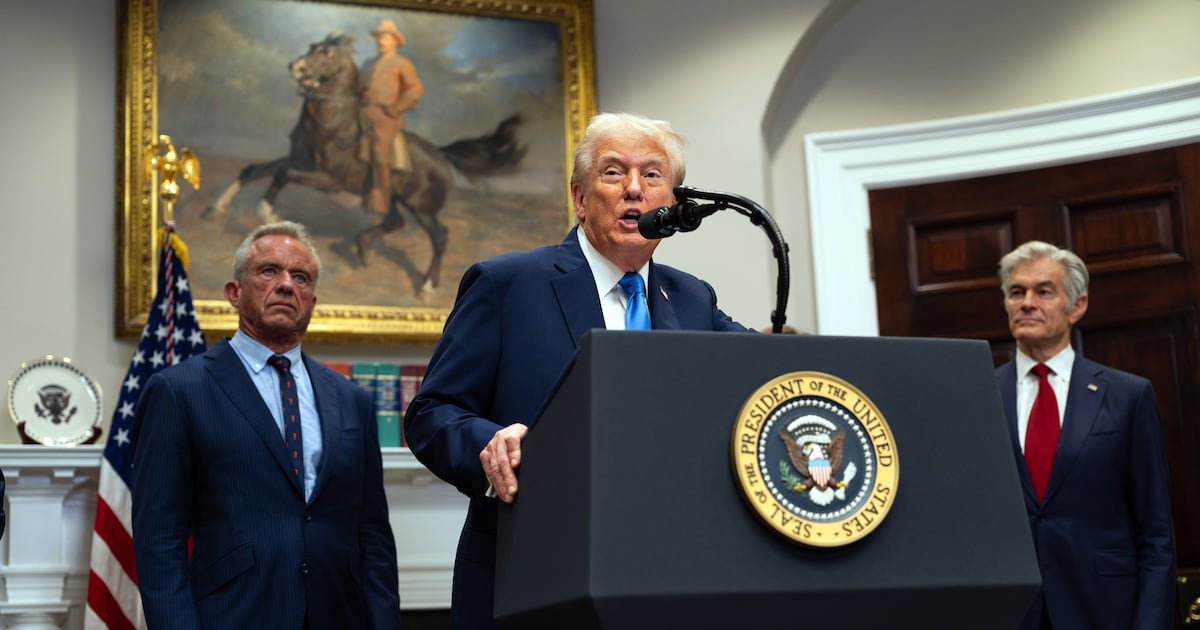

The Irish Times view on Donald Trump’s autism warning: the war on science must be resisted

Read more on post.

Donald Trump’s performance at the White House this week, asserting that a common painkiller is driving a surge in autism, was a particularly egregious piece of political malpractice, even for him. His sweeping claims about acetaminophen were not even reflected in his administration’s own accompanying documentation, which spoke in qualified terms about possible associations and the need for further study.

Outside the US, acetaminophen is sold under its international name, paracetamol, and is generally the first-choice painkiller advised for use during pregnancy following decades of use and large studies showing it is safe at recommended doses.

Citing extensive research, the World Health Organisation said there is no consistent association between acetaminophen use in pregnancy and autism; it advised women to follow the guidance of their doctors and pointedly also reminded the public that vaccines do not cause autism, contrary to claims made by US Health and Human Services secretary Robert F Kennedy jnr.

Research on acetaminophen in pregnancy has produced mixed findings. Some observational studies report associations with later neurodevelopmental diagnoses; others that compare siblings or control better for confounding factors find the association falls away. In clinical terms, the advice given to pregnant women remains unchanged: use necessary medicines judiciously and at the lowest effective dose.

Ireland is governed by EU standards on public health and communication. Those frameworks require strong, reproducible evidence before practice is revised. But unsupported theories like the ones now coming out of the White House do not stop at borders. Similar narratives circulate widely on this side of the Atlantic, often folded into older, discredited vaccine myths. But the record is clear: large studies across many countries have found no causal link.

As for the larger question of why recorded autism rates have risen, the best explanation is multi-layered: diagnostic criteria have expanded; awareness among clinicians and parents has grown; screening has become more routine; social acceptance has encouraged families to seek assessment. These factors explain much of the steep increase in the US and Europe, including Ireland. Specialists also point to a complex interplay of genetic predisposition and broader environmental influences as possible contributors. But that is a research frontier, not a verdict on any single over-the-counter medicine.

When an American president recasts preliminary findings as a simplistic story of cause and effect, public trust inevitably erodes. It is deeply worrying that the forces of irrationality are now in positions of such influence from which to prosecute their war on science.

Opinion

The Irish Times view on the Starmer question: Labour should be careful

Read more on post.

The pressure is mounting on Keir Starmer ahead of the UK Labour party conference starting this weekend. Fifteen months after the party’s landslide general election victory, there are question marks over his continued premiership. Starmer’s vulnerability is partly self-inflicted but it also underlines the challenges he faces.

The UK has registered anaemic growth levels for well over a decade, on the back of a long line of policy mistakes. Prior to the 2024 election, Labour pledged no income tax rises, which has meant a raft of new business taxes, further depressing growth. It also promised 1.5 million new homes by 2029, but construction activity has fallen to its lowest level since the Covid pandemic.

Starmer has had an unfortunate mix of bad luck (losing deputy prime minister Angela Rayner) and bad judgment (the attempt to cut the winter fuel allowance). Labour languishes at 20 per cent in opinion polls while Nigel Farage’s Reform is riding a wave of anti-migrant and anti-establishment sentiment.

To the left, Labour is under threat from the Liberal Democrats and the Greens. It remains to be seen what impact former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn’s new party will have.

Last month, Starmer reshuffled his cabinet in an effort to inject a new sense of purpose. So far there is no tangible signs this is paying dividends.

Just days before the conference starts, Andy Burnham, the popular mayor of Manchester, has launched a scathing attack on Starmer, calling his style of leadership divisive and saying he lacks a credible plan.

The comments are widely seen as an opening salvo in a leadership challenge.

There is no doubt Starmer has made mistakes. But the reality is that Brexit inflicted deep economic wound there are no easy solutions.

The Conservatives elected five different prime ministers in nine years in the mistaken belief that changing personalities would change outcomes. That led to instability and stasis. Labour would do well to remember such a recent lesson.

-

Culture3 days ago

Taylor Swift’s new cinema outing generates more than €12million in just 24 hours

-

Politics3 days ago

European Parliament snubs Orbán with vote to shield Italian MEP from Hungarian arrest

-

Health4 days ago

EU renews support for WHO’s Universal Health Coverage Partnership

-

Culture2 weeks ago

Life, loss, fame & family – the IFI Documentary Festival in focus

-

Culture3 days ago

Twilight at 20: the many afterlives of Stephenie Meyer’s vampires

-

Environment6 days ago

Key oceans treaty crosses threshold to come into force

-

Culture2 months ago

Fatal, flashy and indecent – the movies of Adrian Lyne revisited

-

Culture1 week ago

Farewell, Sundance – how Robert Redford changed cinema forever