Opinion

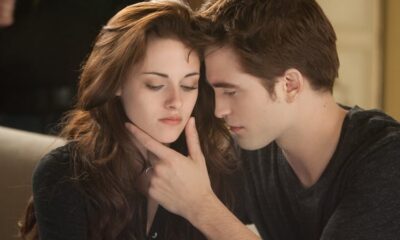

Nigel Farage’s pledge to end indefinite leave could hurt the economy even before an election

Read more on post.

Nigel Farage’s proposal to abolish indefinite leave to remain is a shifting of the goalposts for those who have already come to the UK legally and settled.

Framing issues of migration as a crisis has been beneficial for Farage and other British politicians as a political strategy. However, on this occasion there are early indications that these proposals may provoke a more negative reaction from the British public.

The idea that even those already granted leave to remain would have to reapply creates insecurity for thousands of people who have come to call the UK home, which speaks to some of the human costs of such proposals.

We should also consider the potential implications for the economy. Reform claims billions could be saved by ending the right to apply for permanent residency in the UK – a claim that was called into question within days.

This indicates a pressing need for scrutiny of the economic impact a Reform government would have, particularly given that the party leading in polls.

Polls are not just indicators of who may next occupy 10 Downing Street. They also send signals to key actors in the economy about the country’s potential future direction of travel. And these signals matter. To understand how, we can turn our attention to the questions that an end to indefinite leave to remain may pose for the UK labour market.

There is already a problem with skills investment in the UK. Decisions to invest in skills and training often require a commitment to long-term investment before the employer and the employee realise the benefits.

But what happens to such investment when employers are unsure if their staff may be forced to leave? This is particularly relevant for those key sectors where there is a greater reliance on migrant workers.

Then there is the issue of job creation. If an employer is currently deciding where to invest and create new jobs, one aspect they will consider is access to the skills they need.

We know that there are key areas where employers are concerned about skills shortages in the UK. Would the potential end of leave to remain make it riskier to invest in creating jobs in the UK? This is a question employers will already be asking.

And if you are a worker from another country with skills that are in high demand, would these proposals make the UK more, or less attractive as a destination to bring skills?

These economic implications lead us to a key political question: who did Reform consult before making this announcement?

Reform has consistently sought to position itself as on the side of British business. Did they speak to the Confederation of British Industry about whether scrapping indefinite leave to remain would be a good idea? The Federation of Small Businesses? Did they speak to industry federations in the care sector, the hospitality sector, the education sector, or the health sector, where employers rely upon migrant workers?

Farage has also been keen to present himself as standing up for British workers and has in the past year been seeking to win support of grassroots union members. Did he consult any of the trade unions that represent millions of workers across the UK? Or did he consult trade union representatives in sectors that may be affected by these new proposals?

What type of consultation has informed these new proposals matters because it sends an important signal on the approach to governing that Farage intends to adopt should he become the next prime minister. Such signals are also likely to inform decisions made before the next election by employers and workers sustaining the UK economy.

Alamy/Matthew Chattle

Perhaps owing to the rapid rise of the Reform party and the dominance of two parties in government for generations, it has not received the same degree of scrutiny that previous “governments-in-waiting” have received. But given its dominance in the polls, careful consideration of the impact of its proposals is more necessary than ever.

If we look closer at these latest proposals, we see that they will create a more hostile and uncertain environment for those who have lived and worked in the UK for some years and those considering coming to the country. That may have already created risks for the UK economy.

Want more politics coverage from academic experts? Every week, we bring you informed analysis of developments in government and fact check the claims being made.

Sign up for our weekly politics newsletter, delivered every Friday.

Opinion

Most of gen Z watch TV with the subtitles on – and I understand why | Isabel Brooks

Read more on post.

I used to think there were two types of people: the ones who only use subtitles when necessary, and the unappreciative philistines who use them for no good reason. I was willing to die on this hill, arguing that they distracted from the purity of the audiovisual experience: the cinematographer’s attention to detail, the glimpse of a tear in an actor’s eye, the punchline of an expertly timed joke, and so on.

But I have been forced to recognise just how alone I am on this hill: in 2021, a survey found that 80% of 18-25-year-olds used subtitles all or some of the time, while a new survey run by streaming service U found that 87% of young Britons are using subtitles more than they used to. There is no longer a debate about subtitles: among my peers, “two types” of people have given way to “mostly one type”. (Meanwhile, the 2021 survey found that less than a quarter of boomers used subtitles, despite the latter generation experiencing more hearing difficulties overall.)

Why is this practice so common among people my age? If you aren’t hearing-impaired and are fluent in the language of the dialogue, what is it about subtitles that makes them more appealing?

An easy assumption is that this is the result of a short attention span, passivity and a lazy nature, a failure of generation Zombie. But having experienced watching TV with and without subtitles, I’d say the former doesn’t beget lazy viewing so much as a quicker information download. The new status quo of “subtitles on” among the young reflects both a values shift and cultural conditioning as a result of big tech’s ever-encroaching impact on our entertainment experience.

For example, the small screen in our living room has to share the limelight with the micro screen in our lap. The U survey revealed that 80% of gen Z and millennials “double-screen” when they watch. With subtitles on, I find myself being able to quickly gather what one character has said, look down at my phone, react to a message, then look up before that character has even finished their line. The viewing experience thus becomes multifaceted and efficient. The subtitles allow us to go on our phone but still absorb the content and gist of the TV show. Of course, that means they also function as mini-spoilers: when watching a comedy sketch recently, I found myself half-heartedly chuckling at a joke before it had left David Mitchell’s mouth – because I had already read it on the screen.

I don’t need to use my little grey cells when watching most TV shows, but there are few, like Succession, where double-screening is a sad exercise. Even if I manage to successfully absorb each line in the script through reading, I’d be neglecting the exceptional acting. The same thing cannot be said for Love Island (although arguably the acting is of a high standard there, too).

And social media itself has encouraged the use of subtitles across the board. It is now a given that most creators add text captions to their videos – without the option to turn them off. This cultural shift may explain the generational gap between boomers and younger viewers, the latter only appeased by rapid-fire content and videos with faster cuts, absorbing lightweight content at a higher speed, which text captions allow us to do.

This isn’t simply a trend but a feature anchored in the algorithm itself. Text captions, rather than dialogue, encourage the video to crop up in the TikTok search engine, increasing reach and visibility as well as viewer retention and viewing time. It began as an accessibility improvement, but the rapidity with which it has caught on suggests it’s business-oriented and crucial to getting that sweet algorithm boost. The fact that 85% of social media visual content is now watched on mute (while commuting, cooking, on the treadmill at the gym or in houseshares), coupled with the ease with which AI can generate subtitles without the need for human transcription, means we’re living in a subtitled world – one that is often poorly translated, low-quality and error-ridden.

Seen this way, subtitles have been normalised as a result of our technology-infused lifestyle, rather than being something we have actively sought out or freely adopted. My flatmate, a keen TikToker, said she used to find subtitles distracting and annoying, then gradually started using them while watching TV. “I’ve felt very passive in it,” she said. “I don’t think I look at them most of the time.” Then why do you have the subtitles on, I asked. “I don’t know,” she said with a shrug.

Amazingly, subtitles have not been linked to improvements in young people learning to read, although other studies have shown that they can improve comprehension of what happened in a given programme. Subtitles arguably keep us following more effectively than non-subtitles. Our TV habits are now influenced by a need for efficiency ported over from our social-media habits, which mean we can quickly glean the necessary content and then move on. In a 2023 survey, 40% of Americans cited “enhanced comprehension” as the main reason they use subtitles.

I have to ask: are people now watching shows just to find out what happens, and to prove they’ve seen it? Since when did we finish work, sit down on the sofa, cuddle up and think “thank god, I can’t wait for a bit of comprehension tonight”? TV is supposed to be fun. Shouldn’t we be focused on enjoying it?

-

Isabel Brooks is a freelance writer

Opinion

Farewell Amazon Fresh: the no tills thing was all a bit too awkward | Jason Okundaye

Read more on post.

Amazon Fresh, the till-free grocery shop that uses “just walk out” technology, is closing all 19 of its stores in London, just under five years after opening its first outlet. If you’re unfamiliar, the premise of the store is that shoppers identify themselves at the entrance, walk in, select the items that they want, and then a combination of AI, sensors and computer vision determine the items in their basket and process an automatic payment via a customer’s Amazon account when they walk out.

If that sounds weird and disorienting then I can assure you – having visited an outlet out of pure curiosity and having left distressed – it is. Among the reasons given for the venture’s failure, from location choices to struggling to differentiate itself in the market, one financial analyst has suggested that till-less technology “always felt a little awkward”. When I visited I wasn’t totally clear on how to get in or, frankly, how to get out. A sense of panic overwhelmed me as I wondered if the sensors would process me changing my mind about an item and putting it back on the shelf, or charge me for it. Would I be prosecuted if, say, a large box of cereal blocked the sight of a tin of sardines and thus escaped the sensors?

Of course every store has CCTV equipment, but the idea that sensors and cameras could be connected to my phone and track every item I touched felt like big tech overreach, surveillance on steroids. That you could just walk out of a shop without pressing pay seemed strangely incongruous with the direction of other grocery stores. Around two years ago the big Sainsbury’s down the road installed scan-receipt-to-exit barriers, a technology I had first seen in Paris, and which has been rolled out to many other big supermarkets. It is truly a nightmare. Not only does it feel like you’re going through an airport when you’re just picking up a meal deal, but the scanner is repeatedly faulty, often resulting in a pile-up of people trying to exit.

Then there is the failure of self-scan checkouts. These tills were meant to save time, but that possibility immediately collapses once there’s an “unidentified item in the bagging area” or the overwhelmed shop assistant has to approve someone’s age.

You might then think the idea of a till-free checkout would be a relief. But if anything, when you’re made to feel so distrusted and burdened by inconvenience it feels far more like a setup. No till? Surely someone is waiting on the other side ready to bundle me into a police van over an unscanned pot of pesto pasta.

Mostly though, the failure of Amazon Fresh reveals that we are simply not ready for technology like this. It is the kind of futuristic development that you might have imagined would totally change the face of high street shopping, but shoppers have roundly rejected it. Like our reluctance to take up self-driving cars, it’s about a lack of trust in being totally at the whim of technology. Some stores have been able to win over the public – the Japanese casual wear brand Uniqlo’s self-checkout technology is pretty frictionless and genuinely loved. But even then, as a frequent Uniqlo shopper, while the convenience is nice it makes me feel strangely isolated.

We need, and maybe even like, other people. Whether it’s grocery or clothes shopping, having a little chat or a flirt with a store assistant makes the experience. Recently, after a frustrating and failed attempt to find a suit for a wedding, I soothed myself by spending far too much money on a lovely knitted jumper at Drake’s on Savile Row. The shop assistant told me I looked good in it and, seeing how flustered I was, offered me an espresso. For that alone I’ll be back to blow more of my money.

Of course I don’t expect that treatment on the high street or in a grocery store, but I do find myself missing the small comments of “I love these crisps, my favourite” at a supermarket till. And queueing, though I’ll rue saying this during the post-work rush, is not all bad. One of my favourite things to do in a supermarket queue is peer into other shoppers’ baskets to make a guess about what kind of evening they’re having or what kind of life they live. If you can simply walk out you might save some time, but you’ll learn less about the people around you, while a computer gets to know it all.

after newsletter promotion

-

Jason Okundaye is an assistant newsletter editor and writer at the Guardian. He edits The Long Wave newsletter and is the author of Revolutionary Acts: Love & Brotherhood in Black Gay Britain

-

Politics4 days ago

European Parliament snubs Orbán with vote to shield Italian MEP from Hungarian arrest

-

Culture2 months ago

Fatal, flashy and indecent – the movies of Adrian Lyne revisited

-

Culture3 weeks ago

Life, loss, fame & family – the IFI Documentary Festival in focus

-

Environment1 week ago

Key oceans treaty crosses threshold to come into force

-

Health5 days ago

EU renews support for WHO’s Universal Health Coverage Partnership

-

Culture1 week ago

Farewell, Sundance – how Robert Redford changed cinema forever

-

Culture4 days ago

Twilight at 20: the many afterlives of Stephenie Meyer’s vampires

-

Culture4 weeks ago

What is KPop Demon Hunters, and why is everyone talking about it?