Opinion

Don’t cut them out: lymph nodes may be key to cancer treatment

Read more on post.

Removing lymph nodes during cancer surgery has saved countless lives in many tumour types. Yet recent research is challenging parts of this long-standing practice.

Imagine your body’s immune defences as a city, and lymph nodes as the hubs where police and firefighters gather fresh intel to launch their attack on criminals. What happens if you remove too many of these hubs? This is a new question at the centre of modern cancer surgery.

When surgeons remove lymph nodes, it’s usually for two reasons: to find out whether cancer has spread, and to prevent further spread to other organs. For decades, this approach represented the best standard of care.

If a tumour escapes its original site, cancer cells often travel through lymph vessels and settle in the nearest lymph nodes, which act as biological filters. Detecting cancer cells in lymph nodes signals that a patient’s disease may be more likely to return after treatment.

Removing these nodes allows doctors to “stage” the disease accurately, and potentially increase the chances of eradicating all tumour cells – while also telling oncologists like me to treat the cancer more aggressively.

But lymph nodes are not just passive waystations. They play an active role in the body’s immune response, acting as meeting points for immune cells to share information about cancer. Recent scientific discoveries have led researchers to rethink how crucial these hubs are for sparking powerful, lasting immune reactions.

One of the newest studies shows lymph nodes help maintain a special type of immune cell called “CD8 positive T cells”, which can destroy cancer cells. These immune cells are primed and kept ready to act by the environment inside the lymph nodes.

Without these hubs, the body’s anti-cancer immune response, especially during immunotherapy treatment, may be weaker than previously imagined. The research shows how the specific cells in the lymph nodes make an initial anti-cancer burst of activity. However, this has only been demonstrated in the laboratory, not in humans as yet.

Removing lymph nodes is not without drawbacks. Patients can experience swelling (lymphoedema), increased risk of infection in the affected limb, and sometimes chronic pain or mobility problems. There’s also concern that removing lymph nodes, while reducing short-term risks of cancer spread, might inadvertently weaken the body’s long-term immune defences – especially as modern treatments increasingly rely on the patient’s natural immunity. This is in line with the new study findings.

Why do surgeons still remove lymph nodes, then?

For many types of solid tumour, the risk of metastatic spread remains high, and lymph node involvement is one of the best predictors of cancer recurrence.

Lymph node removal also provides vital information for choosing the most effective post-surgical treatments. In breast cancer, doctors often use a “sentinel node biopsy”. This means removing only the first lymph node that fluid from the tumour drains into. Checking just this sentinel node helps doctors see if the cancer has spread, while reducing the number of nodes removed and lowering the risk of side-effects.

Medical researchers are learning more about how lymph nodes work during long-term illnesses. The new study shows that lymph nodes aren’t just passive filters; they’re active training grounds where special immune cells grow, multiply and become powerful fighters. This is especially important during treatments that boost the immune system, such as checkpoint blockade treatments which are now used for many types of cancer.

These results suggest that taking out lymph nodes doesn’t just block cancer’s spread; it also removes important hubs where the immune system monitors the body and gets reactivated to fight disease.

Over the last decade, hospitals have adopted gentler, more targeted lymph node surgeries. Instead of removing all the nodes in a region, the focus is now on minimising disruption: taking only the nodes most likely to harbour cancer.

This approach reduces complications for patients and may help keep their immunity strong. Some patients with early-stage cancers may even avoid node removal altogether, instead relying on imaging and biopsies to monitor for spread.

For those worried about the consequences of major lymph node removal, emerging therapies offer hope. Immunotherapy drugs, targeted treatments and even cancer vaccines are being developed that can “re-educate” the immune system, even if some lymph nodes have been lost.

Still, there is growing evidence that patients do best when at least some hubs remain – preserving the body’s ability to mount and sustain a defence against lingering cancer cells.

In the future, cancer surgery may become even more personalised. By mapping the activity inside lymph nodes – tracking which ones are essential for immune function and which are most likely to seed new tumours – doctors can tailor surgery so each patient gets maximum benefit with minimum harm.

The recent discoveries challenge surgeons and oncologists to weigh every decision carefully: not just for what is removed today, but for the immunity and future defences left behind.

Is removing lymph nodes in cancer surgery a bad idea? The answer is complex. For many patients, it’s still a good idea and can be lifesaving. But new science teaches us that lymph nodes are more than just staging posts; they may be indispensable for long-term immune protection. The future promises smarter, more strategic surgery, keeping more of the body’s natural defence system intact while targeting cancer with precision.

Opinion

Labour’s plan to revitalise high streets is good – now it has to make sure people hear about it | Morgan Jones

Read more on post.

The government has launched its Pride in Place strategy, which sees significant investment in disadvantaged communities across the country. It is also, says the newly minted housing, communities and local government secretary, Steve Reed, “putting working families in control of their lives and their neighbourhood”. This follows the English Devolution and Community Empowerment bill, which ploughs a similar furrow, legislating for, among other things, communities’ right to buy and ensuring sports venues are automatically listed as assets of community value.

The strategy is being broadly understood as Labour’s answer to Boris Johnson’s much-touted “levelling up”. The investment, Keir Starmer has said, will “get rid of the boarded-up shops, shuttered youth clubs and crumbling parks that have become symbols of a system that stopped listening”. Neighbourhoods and high streets are the place where the “change” promised by Labour’s winning manifesto must first manifest. It’s not all about the fastest-growing GDP in the G7: the strategy starts by asserting that the government’s “measures of success cannot just be shifts in national statistics but must include change that people see and feel in their local community”.

Labour MPs are praising the direct investment the fund will bring to their communities. The funding allocations have been decided by, among other things, the index of multiple deprivation and the lesser-known community needs index, which measures quality of available services. When communicating the policy to their constituents and local media, they are generally leading with the cash amount being funnelled into their areas, as well they should. Money is what makes things real: policies about duties and responsibilities that cost nothing are cheap in all senses of the word.

People working in what might be understood as the “progressive communitarian” space (including organisations such as Power to Change, the Independent Commission on Neighbourhoods, Locality and the Co-operative party) want to critique that narrative, however. They argue that Labour’s plans are different from the levelling-up funds because of the structures by which the money will be spent. It provides money and power.

“Nothing destroys political trust like money that comes and goes,” says Caitlin Prowle, head of politics at the Co-operative party, drawing a direct contrast with Johnson’s plan: “This isn’t just about investment in communities, it’s about a genuine shift in power and ownership. This money comes with new powers to shape and own community assets, so that even when funding fades, the community owns those places and can determine their future.”

As with the provisions of the English Devolution and Community Empowerment bill (but more so), it is being framed by Labour as a response to decreasing trust in politics – and, of course, to Reform UK. Farage’s party placed second to Labour in a great many of the areas that will now receive funding. “This is our alternative to the forces trying to pull us apart,” says Reed in his introduction to the strategy. There are no prizes for guessing who he means.

The theory of change here is based on ideas about political trust, understanding Reform as a manifestation of anti-politics. First, it argues that people want to see real delivery in their local areas – and that at this level it is possible to give it and make people believe politics is responsive to their lives. Second, it seeks to build up trust and positive feeling, from where it is strong at a local level, so that its benefits might apply to national politics.

Steve Reed is a Labour and Co-operative MP, and before entering parliament was leader of Lambeth council, in which time he set up the Co-operative Councils Innovation Network. In 2011, in his contribution to the Purple Book (an attempt at intellectually revitalising the Labour right after the 2010 defeat, featuring contributions from no fewer than five current cabinet ministers), he wrote about “handing more power to communities and the people who use public services”, something which requires turning the “traditional model upside down”.

Reed is a long-term believer in the politics he is now attempting to put into practice; this background probably goes some of the way to explaining why this programme is the most fleshed-out iteration of Labour’s localism-against-Reform playbook thus far. Whether it is successful, however, depends on how well Labour can communicate the agenda and authentically own the changes that will be brought about by this shift of money and power. Reform is, many people acknowledge, significantly ahead of Labour when it comes to community organising (something no doubt due in part to the difficult legacy of the Corbyn-era Labour community organising unit, shuttered early in the Starmer years, which became for many on the then ascendent right of the party a byword for a kind of lefty excess that was both out of touch and insufficiently electorally minded). But the potential rewards are huge: a rebuke to the argument that politicians are removed from people’s real lives, and an injection of cash and autonomy to places that sorely need both.

-

Morgan Jones is the co-editor of Renewal: A Journal of Social Democracy

Opinion

Most of gen Z watch TV with the subtitles on – and I understand why | Isabel Brooks

Read more on post.

I used to think there were two types of people: the ones who only use subtitles when necessary, and the unappreciative philistines who use them for no good reason. I was willing to die on this hill, arguing that they distracted from the purity of the audiovisual experience: the cinematographer’s attention to detail, the glimpse of a tear in an actor’s eye, the punchline of an expertly timed joke, and so on.

But I have been forced to recognise just how alone I am on this hill: in 2021, a survey found that 80% of 18-25-year-olds used subtitles all or some of the time, while a new survey run by streaming service U found that 87% of young Britons are using subtitles more than they used to. There is no longer a debate about subtitles: among my peers, “two types” of people have given way to “mostly one type”. (Meanwhile, the 2021 survey found that less than a quarter of boomers used subtitles, despite the latter generation experiencing more hearing difficulties overall.)

Why is this practice so common among people my age? If you aren’t hearing-impaired and are fluent in the language of the dialogue, what is it about subtitles that makes them more appealing?

An easy assumption is that this is the result of a short attention span, passivity and a lazy nature, a failure of generation Zombie. But having experienced watching TV with and without subtitles, I’d say the former doesn’t beget lazy viewing so much as a quicker information download. The new status quo of “subtitles on” among the young reflects both a values shift and cultural conditioning as a result of big tech’s ever-encroaching impact on our entertainment experience.

For example, the small screen in our living room has to share the limelight with the micro screen in our lap. The U survey revealed that 80% of gen Z and millennials “double-screen” when they watch. With subtitles on, I find myself being able to quickly gather what one character has said, look down at my phone, react to a message, then look up before that character has even finished their line. The viewing experience thus becomes multifaceted and efficient. The subtitles allow us to go on our phone but still absorb the content and gist of the TV show. Of course, that means they also function as mini-spoilers: when watching a comedy sketch recently, I found myself half-heartedly chuckling at a joke before it had left David Mitchell’s mouth – because I had already read it on the screen.

I don’t need to use my little grey cells when watching most TV shows, but there are few, like Succession, where double-screening is a sad exercise. Even if I manage to successfully absorb each line in the script through reading, I’d be neglecting the exceptional acting. The same thing cannot be said for Love Island (although arguably the acting is of a high standard there, too).

And social media itself has encouraged the use of subtitles across the board. It is now a given that most creators add text captions to their videos – without the option to turn them off. This cultural shift may explain the generational gap between boomers and younger viewers, the latter only appeased by rapid-fire content and videos with faster cuts, absorbing lightweight content at a higher speed, which text captions allow us to do.

This isn’t simply a trend but a feature anchored in the algorithm itself. Text captions, rather than dialogue, encourage the video to crop up in the TikTok search engine, increasing reach and visibility as well as viewer retention and viewing time. It began as an accessibility improvement, but the rapidity with which it has caught on suggests it’s business-oriented and crucial to getting that sweet algorithm boost. The fact that 85% of social media visual content is now watched on mute (while commuting, cooking, on the treadmill at the gym or in houseshares), coupled with the ease with which AI can generate subtitles without the need for human transcription, means we’re living in a subtitled world – one that is often poorly translated, low-quality and error-ridden.

Seen this way, subtitles have been normalised as a result of our technology-infused lifestyle, rather than being something we have actively sought out or freely adopted. My flatmate, a keen TikToker, said she used to find subtitles distracting and annoying, then gradually started using them while watching TV. “I’ve felt very passive in it,” she said. “I don’t think I look at them most of the time.” Then why do you have the subtitles on, I asked. “I don’t know,” she said with a shrug.

Amazingly, subtitles have not been linked to improvements in young people learning to read, although other studies have shown that they can improve comprehension of what happened in a given programme. Subtitles arguably keep us following more effectively than non-subtitles. Our TV habits are now influenced by a need for efficiency ported over from our social-media habits, which mean we can quickly glean the necessary content and then move on. In a 2023 survey, 40% of Americans cited “enhanced comprehension” as the main reason they use subtitles.

I have to ask: are people now watching shows just to find out what happens, and to prove they’ve seen it? Since when did we finish work, sit down on the sofa, cuddle up and think “thank god, I can’t wait for a bit of comprehension tonight”? TV is supposed to be fun. Shouldn’t we be focused on enjoying it?

-

Isabel Brooks is a freelance writer

-

Politics4 days ago

European Parliament snubs Orbán with vote to shield Italian MEP from Hungarian arrest

-

Culture2 months ago

Fatal, flashy and indecent – the movies of Adrian Lyne revisited

-

Culture3 weeks ago

Life, loss, fame & family – the IFI Documentary Festival in focus

-

Environment1 week ago

Key oceans treaty crosses threshold to come into force

-

Health5 days ago

EU renews support for WHO’s Universal Health Coverage Partnership

-

Culture1 week ago

Farewell, Sundance – how Robert Redford changed cinema forever

-

Culture5 days ago

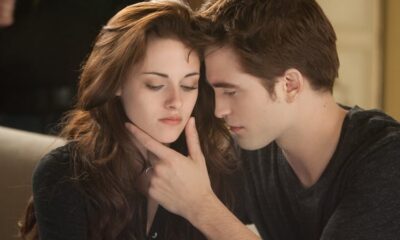

Twilight at 20: the many afterlives of Stephenie Meyer’s vampires

-

Culture4 weeks ago

What is KPop Demon Hunters, and why is everyone talking about it?