Opinion

Dodo 2.0: how close are we to the return of this long extinct bird?

Read more on post.

US biotech company Colossal Biosciences says it has finally managed to keep pigeon cells alive in the lab long enough to tweak their DNA – a crucial step toward its dream of recreating the dodo.

The firm has grown “primordial germ cells” (early embryonic cells) from Nicobar pigeons, the dodo’s closest living relative, for weeks at a time. This is an achievement avian geneticists have chased for more than a decade.

But the breakthrough’s real value lies in its potential to protect wildlife that is still living.

Those cells, once edited, Colossal Bioscience spokespeople say, could be slipped into gene-edited chicken embryos, turning the chickens into surrogate mothers for birds that vanished more than 300 years ago.

The breakthrough arrived with a bold deadline. Colossal Bioscience’s chief executive, Ben Lamm, said the first neo-dodos could hatch within “five to seven years”.

He also spoke of a goal to eventually release thousands on predator-free sites in Mauritius, where dodos lived before they became extinct. The promise sent the start-up’s valuation past US $10billion (£7.4 billion), according to the company’s website.

Almost everything we know about bird gene editing comes from chickens, whose germ cells (cells that develop into sperm or eggs) thrive in standard lab cultures. Pigeon cells typically die within hours outside the body.

Colossal Biosciences says it tested more than 300 combinations of growth factors (substances that stimulate cell multiplication) before finding one that works. Now those cells can be loaded with reconstructed stretches of dodo DNA and molecular “switches” that control skull shape, wing size and body mass.

If the edits take, the modified cells will migrate to an early-stage chicken embryo’s developing ovaries or testes so the surrogate lays eggs or produces sperm carrying the tweaked genome.

That process may create a bird that looks like a dodo, but genetics is only half the story. The draft dodo genome was pieced together from museum bones and feathers. Gaps were filled with ordinary pigeon DNA.

Due to the fact it is extinct and cannot be studied we still don’t know much about the genes behind the dodo’s behaviour, metabolism and immune responses. Recreating the known DNA regions letter by letter would require hundreds of separate edits.

The labour involved would be orders of magnitude more than any agricultural breeding or biomedical programme has ever attempted, although it seems that Colossal Biosciences are willing to throw enough money at the problem.

Lobachad/Shutterstock

There is also the matter of the chicken surrogate. A chicken egg weighs much less than a dodo egg would have. In museum collections there exists only one example of a Dodo egg, and that is similar in size to an ostrich egg.

Even if the embryo survived the early stages, it would soon outgrow the chicken eggshell and be forced to hatch before full development – much like a premature baby that needs intensive care. A chick would therefore need round-the-clock care to reach the historical dodo weight of 10–20kg.

Gene-edited “blank-slate” hens have successfully laid the eggs of rare chicken breeds, showing that germ-cell surrogacy works in principle, but scaling that idea up to a larger, extinct species remains untested.

These caveats are why many biologists prefer the term “functional replacement” to “de-extinction”. What may hatch is a hybrid: mostly Nicobar pigeon, spliced with fragments of dodo DNA, gestated in a chicken.

It might peck and waddle like a dodo and even spread the large fruit seeds that once depended on the original bird. But calling it a resurrection is a marketing exercise rather than science.

Promise v practice

The tension between promise and practice has dogged Colossal Bioscience’s earlier projects. The “dire wolf” puppies unveiled in August 2025 turned out to be grey-wolf clones with a few genetic tweaks. And conservationists have warned that such announcements tempt society to treat extinction as something that is reversible, meaning it is less urgent to prevent endangered species disappearing.

Even so, the pigeon breakthrough could pay dividends for living species. Roughly one in eight bird species is already threatened with extinction, according to BirdLife International’s 2022 global assessment. Germ-cell culture offers a way to bank genetic diversity without maintaining huge captive flocks, and eventually to reintroduce that diversity into the wild.

If the technique proves safe in pigeons, it could help rescue critically endangered birds such as the Philippine eagle or Australia’s orange-bellied parrot. The latter’s wild flock now numbers around 70 birds and dipped to just 16 in 2016.

A spokeswoman for Colossal Biosciences said they remain on track with their scientific milestones but that securing appropriate elephant surrogates and eggs for their woolly mammoth project “involves complex logistics beyond out direct control” and “we prioritise animal welfare throughout, which means we won’t rush critical steps”.

She also said that the firm’s research suggests de-extinction work increases urgency around protecting endangered species. She added: “Critically, we are expanding conservation resources and public engagement, not replacing traditional efforts.

“Our work brings entirely new funding streams into conservation from sources that previously weren’t investing in biodiversity protection. We’ve attracted hundreds of millions in private capital that wouldn’t otherwise go to conservation efforts. Additionally, the genetic tools we develop for de-extinction are already being applied to help endangered species today.”

For Mauritius, any return of dodo-like birds must start with the basics of island conservation. It will be necessary to eradicate rats (which preyed on dodos), control invasive monkeys and restore native forest. Those tasks cost money and need local support but yield immediate benefits for the existing wildlife. Colossal Bioscience must follow through on its commitment to long-term ecological stewardship.

But in the strictest sense, the actual 17th-century dodo is beyond recovery. What the world may see by 2030 is a living experiment, showing how far gene editing has come. The value of that bird will lie not in nostalgia, but in whether it helps us keep today’s species from following the dodo into oblivion.

Opinion

50 years of Linder’s art – feminism, punk and the power of plants

Read more on post.

Currently on show at the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh, Linder’s retrospective Danger Came Smiling showcases half a century of trailblazing art. The exhibition delves into her fascination with plants, inviting the viewer to see beyond traditional notions of gender and sexuality.

For the Liverpool-born artist, there is enchantment in creating imaginary worlds, generating new meanings and inviting others in. Turning toward botanical themes marks a compelling evolution in Linder’s art practice. This new twist fuses a more glamorous side of her punk-feminist roots with symbolic power of the natural world.

Her fascination with plants isn’t just visual, it’s conceptual. In Danger Came Smiling she uses botanical imagery to examine how nature has historically been feminised, controlled and aestheticised, as she explores plant reproduction, horticultural histories and the cultural symbolism associated with flowers.

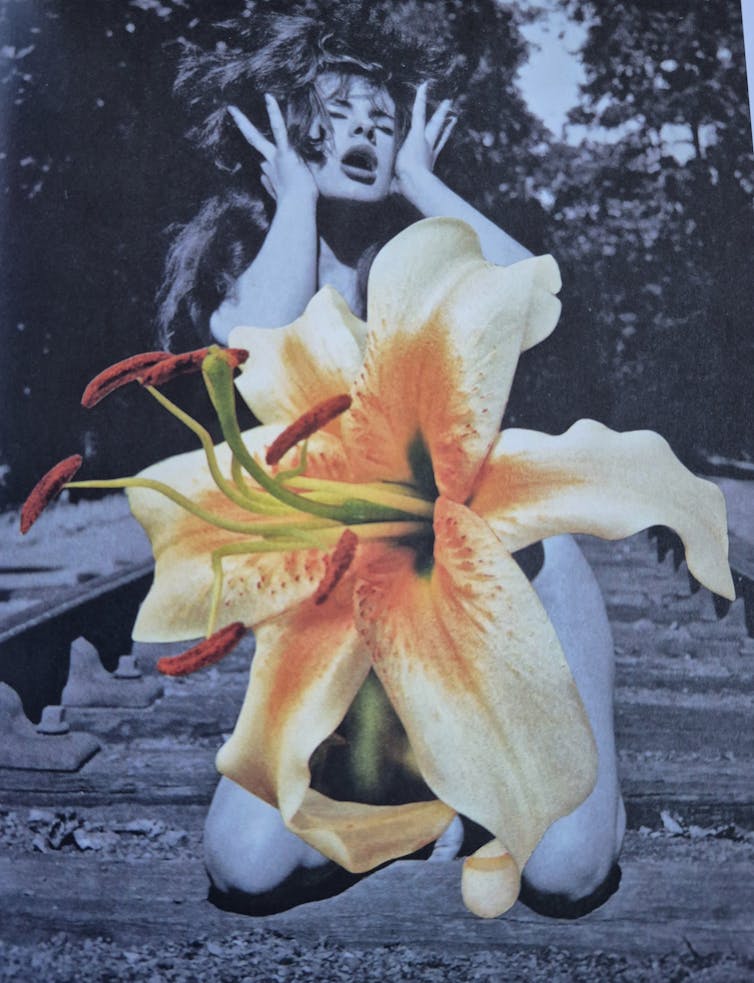

Linder

The Goddess Who Lives in the Mind (2020) features a gigantic lily with stamens protruding from a glamorous woman’s body, while Double Cross Hybrid (2013) reveals an enormous rose blooming out of a woman’s stomach – a monstrous “other” taken away from the domestic space, dressed in botanical themes.

A living critique of gendered power structures – the way access to power, privilege and resources is disproportionately dominated by men – the exhibition is rooted in the organic and the ephemeral, with echoes of her earlier subversive photomontages.

Linder is best known for this disruptive technique – cutting and pasting images from disparate sources to create new, often shocking visual narratives. Her work embodies the radical spirit of early 20th-century European Dada and Surrealists such as Hannah Höch, George Grosz and Dora Maar who pioneered the method, amalgamating images from popular media, magazines and photography into political and satirical statements.

Her critique of the commodification of the female body also draws inspiration from feminist artists such as Hannah Wilke, Carolee Schneemann and Martha Rosler. Here, her photomontages are like jigsaw configurations that blur the boundaries between art, ecology and mythology.

Linder’s outdoor performance A Kind of Glamour About Me was staged to great effect this summer at the opening night of the Edinburgh Art Festival. A dazzling, genre-defying spectacle, it fused Holly Blakey’s visceral choreography, Maxwell Sterling’s haunting soundscapes and Ashish Gupta’s flamboyant fashion. Showcasing an eerie synthesis of body and nature, it turned the Royal Botanic Garden into a site of transformation and storytelling. Here visitors can enjoy it as a video installation.

An improvised take on the myth of Myrrha – the Greek mythological figure who was turned into a myrrh tree after having sex with her father – three dancers in exquisite costumes appear as shifting identities, with one eventually merging into a tree for protection.

Linder draws inspiration from the mythical symbolism of plants. The word glamour in her work comes from the Scots word glamer, which means a magic spell – witches in 16th-century Scotland were hanged for casting “glamer”. Traces of Linder’s photomontage style spill over into the verdant green of the gardens – gigantic lips appear out of nowhere, like a haunting Cheshire cat’s smile.

Linder reclaims women in history and mythology as forbears and heroines. Just like her photomontages, whether in live performance or in video, they are made of parts and fragments that come together in ethereal improvisations.

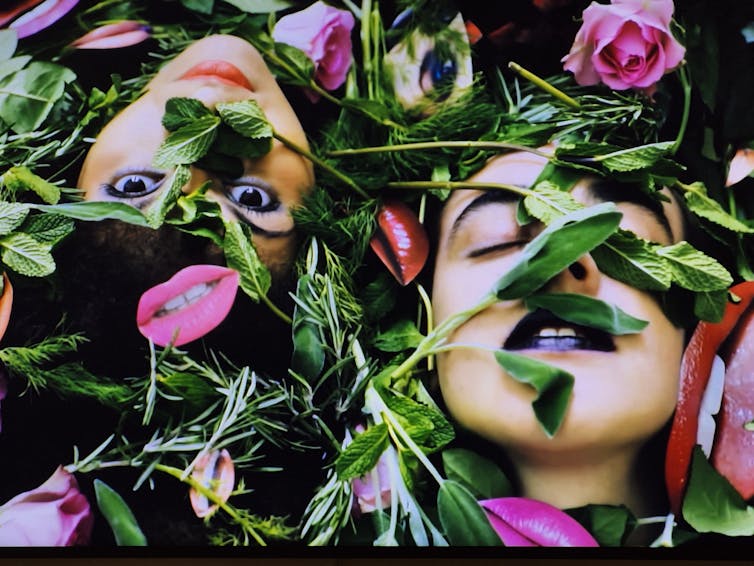

Linder

Her eerie video work Bower of Bliss (2018) is inspired by the detention of Mary Queen of Scots at Chatsworth House in the late 16th century (Linder was in residence there in 2017). In the video, Mary and her custodian Bess of Hardwick are dressed in lavish, colourful costumes designed by Louise Gray. They move to a Maxwell Sterling composition that signals the pleasures and boredom of confinement through clinging, holding and posing. Here we see fabrication mixed with history, witch with knight, warden with prisoner.

Featuring themes of female empowerment and enchantment with nature, Linder’s signature tableaux vivants (living pictures), reveal performers’ dramatically made-up eyes and lips covered with herbs and flowers from the kitchen garden.

Bower of Bliss refers to an enchanted garden from Edmund Spence’s poem The Faerie Queene. The work was originally recreated for Art on the Underground as a billboard at Southwark station in 2018, featuring women who worked on London Underground and performed in the dance work created from it.

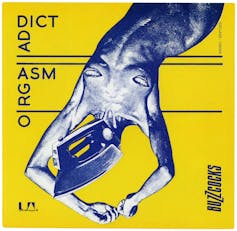

Linder’s newer digital works appear to depart from the DIY-rebellion aesthetic of the radical punk era of the 1970s and early 1980s (such as her iconic Buzzcocks’ Orgasm Addict album cover). Cut-and-paste aggression, visual noise, and an anti-polish vibe were reactions to her life story at the time, when she was fighting the feminist cause.

Alamy

Newer works acknowledge the limitations of punk’s visual language and Linder’s desire to move beyond shock value toward more ritualistic, poetic and nature-infused forms of resistance. She invites us to see plants not as decorative or scientific specimens, but as symbols of survival, sensuality and subversion. These works recycle her artistic technique of combining imagery from domestic or fashion magazines with pornography and other archival material featuring petals, plants or marine life.

Her botanical turn is both a continuation of her feminist sensibility and a new way of engaging with the world, through the slow, radical language of nature. Cleansing the wounds of women represented in her works as well as her own, it leans into the language of plants as a profoundly healing experience.

It is a joy to watch this groundbreaking icon evolve her practice, transformed from an angry young rebel to an accomplished multimedia artist. At the age of 71, Linder continues to challenge societal norms while embracing the beauty and complexity of identity, cementing her legacy as a trailblazer in contemporary art.

Danger Came Smiling is on at Inverleigh House, the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, until October 19, and then transfers to the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea, in November 2025.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Opinion

Do multiple tattoos protect against skin cancer, as a recent study suggests?

Read more on post.

Could tattoos be the secret weapon in the fight against skin cancer? It might sound incredibly unlikely at first, but new research suggests there’s more to tattoo ink than meets the eye, especially when it comes to melanoma risk.

For years, people worried about the possible health dangers of tattoos. But new research suggests something surprising: people with multiple tattoos appear to have less melanoma, not more. However, before anyone rushes to the tattoo parlour for cancer prevention, it’s crucial to take a closer look at the fine print because every study has its flaws, and this one is no exception.

Researchers in Utah – the US state with the highest melanoma rates – studied over 1,000 people. They compared melanoma patients with healthy people to see if tattoos, especially extensive ones, affect cancer risk.

The results suggested that people who’d had multiple tattoo sessions or possessed several large tattoos actually experienced a reduced risk of melanoma. In fact, the risk was more than halved.

This was a striking finding, especially given the longstanding concerns about tattoo inks, which contain chemicals that – in other settings – can be harmful or even carcinogenic. Scientists have previously worried that introducing foreign substances into the skin could promote cancer development.

Extensive recent research has in fact linked tattoos to a type of cancer called lymphoma. But this broad population-based study did not support these fears for melanoma.

Why the results might be misleading

Yet the evidence comes with a number of critical caveats. The first and perhaps most significant issue was the lack of data about key melanoma risk factors, which is essential for drawing reliable cause-and-effect conclusions.

Important risk factors such as sun exposure history, tanning bed use, how easily people sunburn, skin type and family history of melanoma were only recorded for people with cancer – not for the healthy people in the study. Without this information, it’s impossible to tease apart whether the observed lower risk in tattooed people actually stems from the tattoos themselves, or whether it’s merely a byproduct of other lifestyle differences.

Josep Suria/Shutterstock.com

Another issue lies in something called behavioural bias. Tattooed participants were more likely to report riskier sun habits, such as indoor tanning and sunburns, although here the apparent “protection” of multiple tattoos remained even after adjusting for smoking, physical activity and some other variables.

However, data on key risk factors for melanoma, such as sun protection behaviour and the use of sunscreen, weren’t available across both groups. This raises the possibility that the supposedly protective effect might actually be a result of unmeasured differences – perhaps those with many tattoos are more likely to use sunscreen or avoid sun exposure to protect their body art.

Adding further complexity, the response rate among melanoma cases was only about 41%, meaning that most people with melanoma didn’t answer questions about it, which is relatively low, though typical for studies using surveys like this. This could create what’s called selection bias. If people who answered the survey were different from those who didn’t, the results might not apply to everyone.

No information was collected on where the tattoos were located, so we don’t know if they were on sun-exposed or covered areas of the body – an important distinction since ultraviolet light is a major risk factor for skin cancer. In fact, recent research suggests air pollution may protect from melanoma and it does this by filtering out harmful UV rays.

Interestingly, the study did not show that melanomas occurred any more frequently within tattooed skin than in un-tattooed areas. This suggests that tattoo ink itself is unlikely to be directly carcinogenic, though some research suggests that it might be.

However, the researchers urge caution. This is one of the first major studies on tattoos and melanoma, so the results suggest new ideas to test rather than prove that tattoos are protective.

Comparisons with previous research, conducted in other countries, also reveal inconsistent findings. Some studies have shown skin cancers – including melanoma – in tattooed populations or areas of the body. However, these studies have also been hampered by small sample sizes, lack of information on other key risk factors, and diverse sun-bathing habits around the world.

What does this all mean in practical terms? The findings are far from a green light to seek out tattoos as a shield against melanoma. Crucially, the absence of detailed behavioural and biological data means that the observed effects could just as easily reflect differences in lifestyle or unrecorded habits in tattooed populations.

For now, the fundamental advice for melanoma prevention is unchanged: limit sun exposure, wear sunscreen, and check your skin regularly, regardless of ink status.

For those who already have multiple tattoos, the study does, however, provide some reassuring news: there is currently no evidence that tattooing increases the risk of melanoma, and any association with reduced risk may simply reflect other factors.

The broader message, though, is one of scientific caution. Interesting signals like these warrant further investigation in larger, more carefully controlled studies, that can fully account for all the complexities of cancer risk and human behaviour. Until then, tattoos may remain a personal choice, but definitely not a medically endorsed strategy for staving off skin cancer.

Opinion

Geography and politics stand in the way of an independent Palestinian state

Read more on post.

There has been a recent rush of countries to formally recognise the state of Palestine. Affirming Palestinian sovereignty marks a historic diplomatic milestone, yet the exact layout of its territory, a central requirement under international law, remains fiercely contested from every hilltop in the West Bank to the ruins of Gaza.

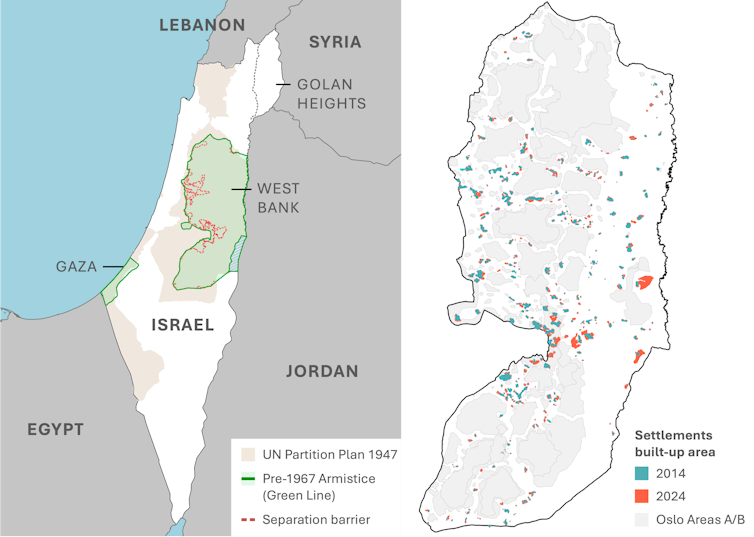

To grasp what this moment means, we need to trace how borders have evolved – or dissolved – over Palestine’s tumultuous political history. The 1947 UN partition plan had envisioned two semi-contiguous territories for Jewish and Arab states, with Jerusalem as an international city.

But that vision quickly collapsed into the war that led to the establishment of Israel in 1948. Palestinians found themselves confined to the West Bank and Gaza Strip as fully separated territories, demarcated by the “green line” and placed under Jordanian and Egyptian control.

These initial contours remain the internationally recognised basis for Palestinian statehood until today – and are referred to as the “pre-1967 borders”. That year, the six-day war saw Israel effectively tripling its territory. It occupied all of the West Bank and Gaza Strip and annexed East Jerusalem.

Israeli settlements immediately began fragmenting Palestine’s geography, especially in the West Bank. These settlements are illegal under international law, and in many cases lacked even the government’s authorisation.

Yet they faced limited government pushback – and were often directly supported by Israeli authorities. The Oslo accords later carved the territory into Areas A, B, and C with varying degrees of Palestinian governance.

Following suicide bombings during the second intifada (2000-05), Israel built a separation barrier cutting deep inside the 1967 borders. Six decades on, the West bank resembles a fragmented archipelago more than a cohesive state territory.

Mallock & Krekel (2025)., Author provided (no reuse)

Building insecurity

In a recent study, my colleagues and I used satellite imagery to show, for the first time, what exactly this does to the West Bank. We tracked all 360 settlements and outposts that existed in 2014 across the following decade.

During this time alone, the average settlement expanded by two-thirds in size. Collectively, they now occupy 151 sq km of built-up area – compared to 88 sq km ten years ago – a 72% increase. Adding to this are hundreds of new settlements, especially with a wave of approvals following October 7 2023.

Each of these settlements comes with extensive Israeli military presence and infrastructure. This has created a complicated system of roads and checkpoints that typically exclude Palestinians, severely restricting movement and economic activity.

What’s worse, violent attacks and harassment by extremist settlers are well documented in some locations. To say that building an independent state under these conditions is challenging would be a massive understatement.

A recently approved development project on the West Bank exemplifies this. On paper, the E1 project it will be yet another settlement. But if constructed, E1 – short for “East One” – will choke off the main road running north to south outside Jerusalem, effectively cutting the West Bank in half.

Israel’s far-right finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, celebrated the move as “erasing” the idea of a Palestinian state while bolstering national security – the government’s official justification for settlement expansion.

Read more:

Israel’s plan for massive new West Bank settlement would make a Palestinian state impossible

In reality, the settlements have the exact opposite effect. Our research, involving four months of fieldwork and surveying over 8,000 Palestinians, found an alarming dynamic. Living within a few kilometres of settlements almost doubled the likelihood of engagement in high-risk and violent action (more than 82%), while moderate protest dropped by 30-36%. Similarly, support collapsed for diplomatic initiatives, and surged for violent attacks.

Critically, this isn’t simply a reaction to settler violence. Beyond the effects of such exposure, settlement presence alone intensified collective moral outrage, a cognitive state known to drive violent conflict.

Studies demonstrate how this state primes people to think in terms of threat and punishment rather than the risks of taking action – particularly dangerous in the West Bank. And this factor is likely to persist: the settler community today counts upwards of half a million people, many of them armed, violence prone, and radically opposed to leaving.

What this implies for Israeli-Palestinian relations is that, as settlements expand, so will political violence and retaliation, fuelling further cycles of conflict. The recent attack in Jerusalem, in which Palestinian gunmen shot six people just weeks after E1’s approval, tragically shows this reality already.

Looking for leaders

Any viable Palestinian state must include a vision for Gaza’s reconstruction and integration once the horrific suffering and famine caused by Israel’s brutal attacks ends. Yet as I’ve reported based on data collected in January, Gaza’s largest political constituency (32%) now consists of those who feel represented by nobody.

Hamas is militarily decimated and has lost almost all remaining support among the public. The UK and other countries have also proscribed the terrorist group. Yet no viable alternative has emerged to represent Gazans’ interests.

EPA/Tolga Akmen

Over in the West Bank, a Palestinian Authority (PA) dominated by elderly men offers little better. Three decades since its establishment as part of the Oslo peace process, it is widely seen as illegitimate, corrupt and incapable, as polls consistently show.

The most realistic governance scenario involves a restructured PA administering both territories. It’s likely this will still be dominated by Fatah but with fundamentally reformed structures and leaders.

If elections were held today, the 89-year-old president, Mahmoud Abbas, would almost certainly lose. One candidate with more prospects is the imprisoned Marwan Barghouti, complicating succession planning.

Whoever eventually leads a unified Palestine will inherit decades of failed self-governance, deep public scepticism, and Israel undoubtedly attempting to intervene in this process.

Making recognition matter

Despite massive challenges, building a functioning Palestinian state is not impossible. So recognition can be more than a symbolic act. Already, it’s reshaping in tangible ways how major powers engage with Palestinian representatives while applying meaningful pressure on Israel’s leaders.

But as nations line up to recognise Palestine, they must confront what they’re actually recognising. Given the vicious cycles of settlement expansion and violence that our research shows, recognition risks becoming an empty gesture unless this issue is addressed diplomatically head on. Without creating genuine conditions for statehood that uphold the interests of all parties, neither goal will be achieved.

The choice is no longer between one-state and two-state solutions. It’s between recognising borders that have long been rendered meaningless – or committing to build something viable. Both the future of Palestinian statehood and Israeli security may depend on that choice.

-

Culture2 days ago

Taylor Swift’s new cinema outing generates more than €12million in just 24 hours

-

Environment1 week ago

Chimps drinking a lager a day in ripe fruit, study finds

-

Politics2 days ago

European Parliament snubs Orbán with vote to shield Italian MEP from Hungarian arrest

-

Culture2 weeks ago

Life, loss, fame & family – the IFI Documentary Festival in focus

-

Health3 days ago

EU renews support for WHO’s Universal Health Coverage Partnership

-

Culture2 days ago

Twilight at 20: the many afterlives of Stephenie Meyer’s vampires

-

Environment6 days ago

Key oceans treaty crosses threshold to come into force

-

Culture2 months ago

Fatal, flashy and indecent – the movies of Adrian Lyne revisited