Environment

Scientists pinpoint the brain’s internal mileage clock

Read more on post.

Scientists have for the first time located the “mileage clock” inside a brain – by recording the brain activity of running rats.

Letting them loose inside a small, rat-sized arena, the researchers recorded from a part of their brains that is known to be important in navigation and memory.

They found that cells there “fired” in a pattern that looked like a mileage clock – ticking with every few steps the animal travelled.

A further experiment, where human volunteers walked through a scaled up version of this rat navigation test, suggested that the human brain has the same clock.

This study, published in the journal Current Biology, is the first to show that the regular ticking of “grid cells”, as they are known, is directly connected to the ability to correctly gauge the distance we’ve travelled.

“Imagine walking between your kitchen and living room,” said lead researcher Prof James Ainge from the University of St Andrews. “[These cells] are in the part of the brain that provides that inner map – the ability to put yourself in the environment in your mind.”

This study provides insight into exactly how that internal map in our brains works – and what happens when it goes awry. If you disrupt the ticking of that mileage clock by changing the environment, both rats and humans start getting their distance estimation wrong.

In real life, this happens in darkness, or when fog descends when we’re out on a hike. It suddenly becomes much more difficult to estimate how far we have travelled, because our mileage counter stops working reliably.

To investigate this experimentally, researchers trained rats to run a set distance in a rectangular arena – rewarding the animals with a treat – a piece of chocolate cereal – when they ran the correct distance and then returned to the start.

When the animals ran the correct distance, the mileage-counting cells in their brains fired regularly – approximately every 30cm a rat travelled.

“The more regular that firing pattern was, the better the animals were at estimating the distance they had to go to get that treat,” explained Prof Ainge.

The researchers were able to record the brain’s mileage clock counting the distance the rat had moved.

Crucially, when the scientists altered the shape of the rat arena, that regular firing pattern became erratic and the rats struggled to work out how far they needed to go before they returned to the start for their chocolate treat.

“It’s fascinating,” said Prof Ainge. “They seem to show this sort of chronic underestimation. There’s something about the fact that the signal isn’t regular that means they stop too soon.”

The scientists likened this to visual landmarks suddenly disappearing in the fog.

“Obviously it’s harder to navigate in fog, but maybe what we what people don’t appreciate is that it also impairs our ability to estimate distance.”

To test this in humans, the researchers scaled up their rat-sized experiment. They built a 12m x 6m arena in the university’s student union and asked volunteers to carry out the same task as the rats – walking a set distance, then returning to the start.

Just like rats, human participants were consistently able to estimate the distance correctly when they were in a symmetrical, rectangular box. But when the scientists moved the walls of their purpose-built arena to change its shape, the participants started making mistakes.

Prof Ainge explained: “Rats and humans learn the distance estimation task really well, then, when you change the environment in the way that we know distorts the signal in the rats, you see exactly the same behavioural pattern in humans.”

As well as revealing something fundamental about how our brains allow us to navigate, the scientists say the findings could help to diagnose Alzheimer’s Disease.

“The specific brain cells we’re recording from are in one of the very first areas that’s affected in Alzheimer’s,” explained Prof Ainge.

“People have already created [diagnostic] games that you can play on your phone, for example, to test navigation. We’d be really interested in trying something similar, but specifically looking at distance estimation.”

Environment

China, world’s largest carbon polluting nation, announces new climate goal to cut emissions

This post was originally published on this site.

Environment

Indigenous women in Peru use technology to protect Amazon forests

This post was originally published on this site.

Environment

China makes landmark pledge to cut its climate emissions

Read more on post.

Mark Poynting and Matt McGrathBBC News Climate and Science

European Photopress Agency

European Photopress AgencyChina, the world’s biggest source of planet-warming gases, has for the first time committed to an absolute target to cut its emissions.

In a video statement to the UN in New York, President Xi Jinping said that China would reduce its greenhouse gas emissions across the economy by 7-10% by 2035, while “striving to do better”.

The announcement comes at a time the US is rolling back on its commitments, with President Donald Trump on Tuesday calling climate change a “con job”.

But China’s plan has been met with disappointment from environmentalists as it falls far short of what would be needed to meet global climate goals.

“Even for those with tempered expectations, what’s presented today still falls short,” said Yao Zhe, global policy adviser at Greenpeace East Asia.

While the year’s big gathering of global leaders will be at COP30 in Brazil in November, this week’s UN meeting in New York has extra relevance because countries are running out of time to submit their new climate plans.

These pledges – submitted every five years – are a key part of the Paris climate agreement, the landmark deal in which nearly 200 countries agreed steps to try to limit global warming.

The original deadline for these new commitments – covering emissions cuts by 2035 – was back in February, but countries are now scrambling to present them by the end of September.

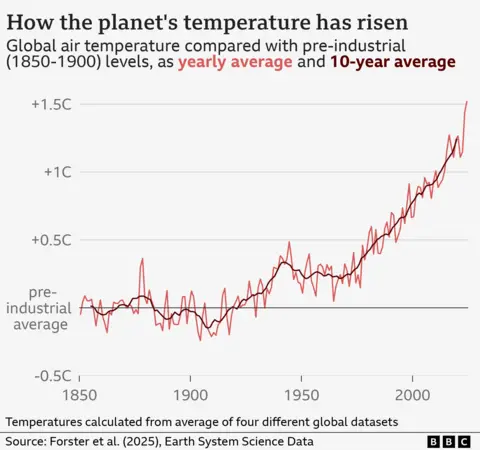

Speaking before the meeting UN Secretary-General António Guterres said the pledges were critical to keep the long-term rise in global temperatures under 1.5C, as agreed in Paris.

“We absolutely need countries to come […] with climate action plans that are fully aligned with 1.5 degrees, that cover the whole of their economies and the whole of their greenhouse gas emissions,” he said.

“It is essential that we have a drastic reduction of emissions in the next few years if you want to keep the 1.5 degrees Celsius limit alive,” he added.

As the world’s biggest emitter, China’s plans are key to keeping this goal in sight.

Back in 2021, President Xi announced that China would aim to peak its emissions this decade and reach “carbon neutrality” by 2060.

Today’s pledge marks the first time that China has set actual emissions reductions targets on that path.

“These targets represent China’s best efforts based on the requirements of the Paris agreement,” President Xi said.

It also covers all greenhouse gases, not just carbon dioxide, and will be measured “from peak levels” of emissions – the timing of which President Xi did not specify.

He added China would:

- expand wind and solar power capacity to more than six times 2020 levels

- increase forest stocks to more than 24bn cubic metres

- make “new energy vehicles” the mainstream in new vehicle sales

Off track for 1.5C

Such is the scale of China’s emissions that any reduction would be significant in climate terms.

China was responsible for more than a quarter of planet-warming emissions in 2023, at almost 14bn tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent.

A 10% reduction in China’s emissions would equate to 1.4bn tonnes a year, which is nearly four times the UK’s total annual emissions.

But China’s new target does fall short of what would be needed to meet international climate goals.

“Anything less than 30% is definitely not aligned with 1.5 degrees,” said Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

Most scenarios to limit warming to 1.5C – or even well below 2C – would require China to make much greater cuts than that by 2035, he added.

In many cases, that would mean more than a 50% reduction.

It is further evidence of the gap between what needs to be done to meet climate targets and what countries are planning.

Earlier this week, a report by the Stockholm Environment Institute warned that governments around the world are collectively planning to produce more than double the amount of fossil fuels in 2030 than would be in line with keeping to 1.5C.

Ramp-up of renewables

What gives some observers hope is that China has a track record of exceeding many of its international climate commitments.

It had, for example, pledged to reach a capacity of 1,200 gigawatts for wind and solar power by 2030. It smashed through that goal in 2024 – six years early.

“The targets should be seen as a floor rather than a ceiling,” said Li Shuo, director of China Climate Hub at the Asia Society Policy Institute.

“China’s rapid clean tech growth […] could propel the country much further over the coming decade,” he added.

“China’s 2035 target simply isn’t representative of the pace of the energy transition in the country,” agreed Bernice Lee, distinguished fellow and senior adviser at Chatham House.

“There’s a case to be made that Beijing missed a trick in landing a more ambitious goal as it would have won broad global praise – a stark contrast to the US,” she added.

While China ramps up its renewables, it continues to rely heavily on coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel.

Last year saw China’s electricity generation from coal hit a new record – although initial data suggests it has fallen in the first half of 2025 amid a surge in solar electricity.

“There is also mounting evidence that the country’s emissions are plateauing, with this year’s levels expected to be lower than in 2024,” said Li Shuo.

Today’s new target signals “the beginning of decarbonisation after decades of rapid emissions growth”, he added.

-

Culture1 day ago

Taylor Swift’s new cinema outing generates more than €12million in just 24 hours

-

Politics1 day ago

European Parliament snubs Orbán with vote to shield Italian MEP from Hungarian arrest

-

Culture1 day ago

Milan Fashion Week 2025: Unmissable shows and Giorgio Armani in mind

-

Culture2 days ago

Marvel stars Mark Ruffalo and Pedro Pascal stand up for Jimmy Kimmel as Disney boycott intensifies

-

Business11 hours ago

Households to be offered energy bill changes, but unlikely to lead to savings

-

Travel & Lifestyle1 day ago

New York City’s Most Iconic Foods—and Where to Get Them

-

Other News1 day ago

Germany updates: Finance minister defends 2026 budget plans

-

Travel & Lifestyle1 day ago

At the Marrakech International Storytelling Festival, an Ancient Tradition Finds New Life