Opinion

The Irish Times view on the presidential election: the battlelines are drawn

Read more on post.

And then there were three. Following an extended phoney war in the run-up to nominations closing this week, the battleines have now been drawn for the presidential election.

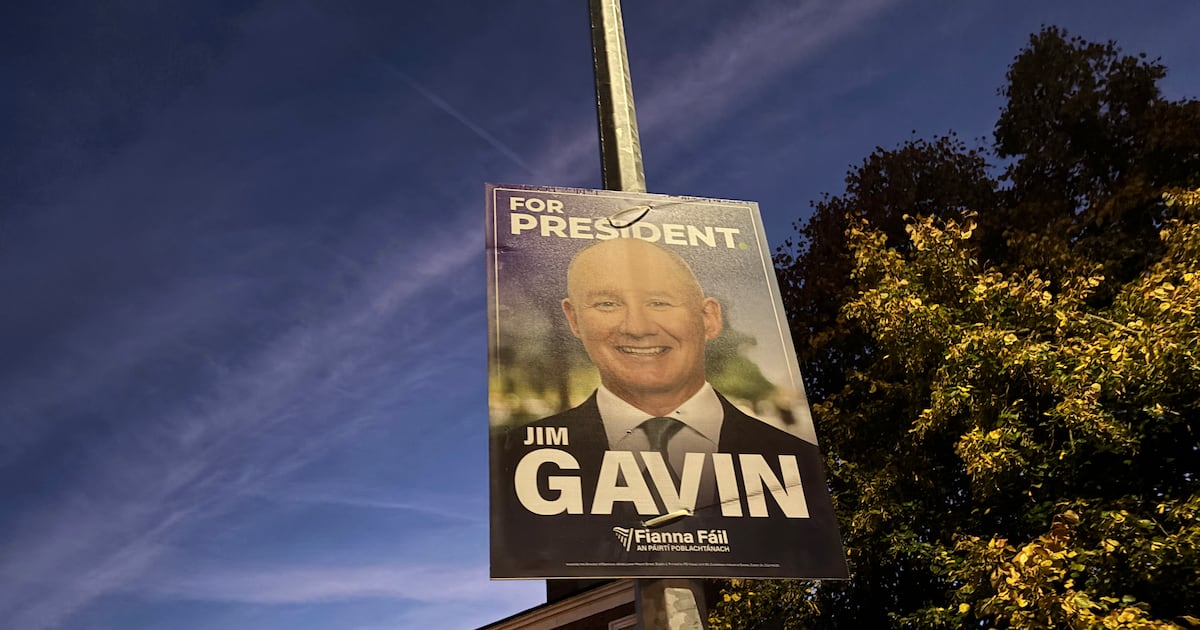

Four weeks from today, ballot boxes will be opened to reveal whether Catherine Connolly, Jim Gavin or Heather Humphreys will be Ireland’s 10th president.

At this point, all three will believe that victory is within their grasp. Connolly has assembled an impressively broad coalition of left-wing parties behind her and thus far has run the most modern and energetic campaign, with a string of public engagements including some high-profile podcasts. Her use of social and digital media seems well ahead of her rivals, reflecting a focus on younger voters who are more likely to be energised by her message on a range of subjects from Gaza to neutrality.

The campaigns of Humphreys and Gavin have been quieter. Humphreys has relied heavily on personality and biography. The former Fine Gael minister presents herself as a warm and familiar presence, focusing on local interactions and family history while rarely straying into policy. Gavin, making his electoral debut, is even more of an unknown quantity. Whether Micheál Martin’s decision to put forward the former Dublin football manager proves astute or naive will become clear in the coming weeks.

Both candidates appear to be keeping their powder dry. They declined to challenge Connolly’s recent controversial remarks on Hamas and German military spending. Their calculation may well make sense. In a contest almost certain to be decided by transfers, there is little to gain and much to lose by alienating voters too early. They may also believe that the election will be won or lost in the final 10 days of the campaign, when less committed voters finally begin to focus on their choice.

That strategymay be correct but carries its own hazards. Neither Gavin nor Humphreys has yet demonstrated the ability to capture the public mood with empathy and vision in the way the last three presidents did when seeking office. Mary Robinson, Mary McAleese and Michael D Higgins each offered a forward-looking, unifying message that voters could rally behind. It is not yet clear which of today’s contenders can match that feat. Already, all three have stumbled over quite basic questions on the campaign trail.

The first televised debate on Monday will be the electorate’s initial chance to judge them side by side. It will test Connolly’s positions, reveal whether Gavin can rise to the national stage and show if Humphreys can convert personal warmth into a compelling national message. For now, the race remains finely balanced, with the decisive moves still to come.

Opinion

The Irish Times view on Shakespeare and the Leaving Cert: hang on to the Bard

Read more on post.

Minister for Education Helen McEntee is correct to dismiss the proposal to drop the compulsory study of Shakespeare from the higher-level Leaving Certificate English syllabus. Her response recognised what the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment’s draft specification appeared to forget: the work of the world’s greatest dramatist is a central pillar of literary education.

The context makes this more pressing. International research has pointed to a worrying decline in reading ability across English-speaking countries, with falling comprehension and limited critical vocabulary. Why would any educational authority wish to hasten that process by reducing exposure to challenging and enriching literature?

There appears to be a pattern here. A few years ago, former education minister Joe McHugh overruled the same body’s recommendation that history should not be a core subject in the revised Junior Cycle syllabus. That earlier decision, like McEntee’s now, recognised the value of giving all students a firm grasp of the cultural and historical forces that shape their world. It is worth asking whether this impulse to sever connections with the past is truly in the interests of young people.

Supporters of the proposed change argue for flexibility and a broader range of modern voices. But the Leaving Certificate has already successfully widened its reach, giving space to more contemporary writers. There is no reason why such progress should come at Shakespeare’s expense.

His plays demand rigorous engagement. They teach students to read closely, to follow complex arguments, to recognise ambiguity and debate conflicting interpretations. Their exploration of ambition, jealousy, love and power still resonates. And they anchor students in a literary tradition that informs everything that has followed.

The proposal the Minister rejected would have narrowed, not widened, horizons. Future revisions should build on the principle of a rich and inclusive syllabus that can add new voices without discarding the foundations on which literary education rests.

Opinion

It’s a jungle out there: Sorcha Pollak on growing up fast while working in the Amazon at 18

Read more on post.

Almost exactly 20 years ago, September 9th, 2005, to be exact, I stepped on board a flight that whisked me away from the secure, safe and reliably predictable first 18 years I’d spent on this earth.

Three months after sitting the Leaving Cert, when most of my peers were returning from post-exam holidays and making final arrangements before embarking on university life, I set off for South America.

In many ways September 9th was the day my journalism career began. With no mobile phone and limited access to a landline in my new Peruvian home, I kept a weekly blog of my experiences working with children in Iquitos, a city deep in the Amazon jungle, accessible only by plane or boat. In 2005, writing a blog was still a novel endeavour, at least within my social circle.

It offered a young, aspiring writer the blank page to share her ideas and experiences without (too much) judgment. These were the days before angry keyboard warriors. Let’s be honest, the small number that did exist had no interest in the idealistic musings of a Dublin teenager.

Social media and smartphones had not yet taken over our lives. Facebook only became available for a small number of Irish students in 2006. Before this, we occasionally logged into the slow-moving, clunky Bebo on our parents’ desktop computers.

Households lucky enough to own a computer often relied on a modem connection. In short, people’s lives were not yet posted in real time, communication could truly be cut off and one could genuinely disappear into a jungle and rely primarily on letters and care packages containing newspaper cuttings for contact with the outside world.

Each Saturday, after a week of homework clubs, music lessons, toddler nappy changes and poorly dubbed movies, my fellow volunteer and I took a motor-taxi down the dusty, unpaved Avenida José Abelardo Quinones to Iquitos’s Plaza Mayor, where we spent two sweaty hours writing emails and blog posts and catching up with family members on MSN chat.

From there, we headed to the bustling Belén market to pick up our papaya and mango supply for the week, often stopping by the bank or cinema lobby to avail of the cool, air-conditioned air pumped into only a handful of city centre buildings.

While temperatures rarely exceeded 35 degrees in Iquitos, the daily humidity hovered between 85-90 per cent and our electric fan broke early in the year. My teenage body was forced to quickly acclimatise and two decades on, I still enjoy my deepest sleeps when visiting hot climates.

The heat wasn’t all bad – it forced us to explore the tributaries of the Amazon in long wooden canoes with newly found friends, seeking out swim spots where we spent afternoons munching on fried plantain and sipping glass bottles of Inca Kola – a bubblegum-flavoured, highly addictive, yellow soda that remains a staple beverage across Peru.

The twice-to-three-times-weekly power cuts, often leaving us without light or running water, were just another quirk of jungle city life.

I was undeniably homesick – for my parents, my sister, pasta and Dairy Milk. I was confronted with grief for the first time in my young life, mourning the loss of my grandmother while her funeral was held in a Dublin church thousands of miles away.

I kept getting sick and ending up on a drip in the crowded and chaotic local hospital (they eventually discovered a parasite had set up camp in my gut). But yet, I loved it all.

Earlier this month I spent 36 hours in Manchester with the two women I shared that year with. The Mancunian I lived with, another naively idealistic 18-year-old who was forced to become my unofficial carer during those regular hospital visits, is now an emergency transplant nurse. There was prescience in her caring abilities.

Our conversation over those two days meandered between children, pregnancy, miscarriages, housing costs, job struggles and relationship grievances. All the topics you’d expect a trio of western white women in their late 30s to discuss.

But every now and then, our chats would diverge in a different direction, to recollections of hiking through landslides, drinking in bars hanging over the banks of the Amazon, hallucinations caused by our daily dose of Larium – an antimalarial drug that was subsequently withdrawn from sale – and being abducted by a gun-carrying criminal gang in the Bolivian capital of La Paz on the eve of the election of Evo Morales in 2005 (this actually happened).

I prefer not to reflect too much on what might have followed had a female police officer, who happened to be walking by the vehicle we’d been held in, not knocked on the window.

[ An Irish woman in Peru: ‘I found it easy setting up a business here’Opens in new window ]

And then there were the seemingly more mundane tasks of life in Iquitos – the weekly routine of caring for young children abandoned by their families in the “Aldea” where we lived and worked.

“Do you remember we used to walk the kids on a Sunday to the local prison to visit their parents,” asked my friend, recalling a memory I had totally erased from my mind.

Even today, the names of those children, some of whom were adopted outside Peru to countries around the world, names such as Orlando, Danisa and Luis, remain imprinted in my mind. Forever associated with the smiling faces that greeted me every morning for 12 months.

We also spoke of our admiration for our parents who allowed their teenage girls to quite simply disappear abroad. Years after my return, my unceasingly stoic mother admitted she cried herself to sleep for weeks following my departure. We 1980s millennials were not yet privy to the phenomenon of helicopter parenting. Lucky us.

[ Helicopter, free-range, concierge, lighthouse: What kind of parent are you?Opens in new window ]

-

Culture3 weeks ago

Life, loss, fame & family – the IFI Documentary Festival in focus

-

Politics4 days ago

European Parliament snubs Orbán with vote to shield Italian MEP from Hungarian arrest

-

Culture2 months ago

Fatal, flashy and indecent – the movies of Adrian Lyne revisited

-

Environment1 week ago

Key oceans treaty crosses threshold to come into force

-

Health4 days ago

EU renews support for WHO’s Universal Health Coverage Partnership

-

Culture4 days ago

Twilight at 20: the many afterlives of Stephenie Meyer’s vampires

-

Culture1 week ago

Farewell, Sundance – how Robert Redford changed cinema forever

-

Culture4 weeks ago

What is KPop Demon Hunters, and why is everyone talking about it?