Opinion

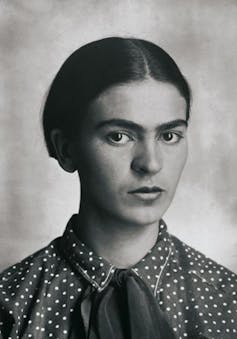

Frida Kahlo’s record-breaking El Sueño redefines intimacy by making death a permanent roommate

DCM Editorial Summary: This story has been independently rewritten and summarised for DCM readers to highlight key developments relevant to the region. Original reporting by The Conversation, click this post to read the original article.

Frida Kahlo’s 1940 painting *El Sueño (La Cama)*, or *The Dream (The Bed)*, recently sold at Sotheby’s New York for $54.7 million, becoming the most expensive Latin American artwork and setting a new auction record for a female artist. Included in the “Surrealist Treasures” collection, the painting features a haunting scene you might interpret as a surreal nightmare—a skeleton resting above a sleeping woman. However, the work offers more than surrealism. You’re confronted with themes of life, death, and Mexican cultural symbolism embedded in Kahlo’s distinct visual language.

When you look at the painting, you see a bed, seemingly floating in a cloudy sky, divided into two realms. The upper portion, light and ethereal, holds a skeleton arranged like a suitor – complete with flowers and wires resembling explosives. Meanwhile, Frida Kahlo lies beneath, wrapped in a thorn-laced blanket, surrounded by plant-like roots. The duality of the scene, with both figures facing the same way, suggests a mirroring of life and death. The skeleton you see isn’t fictional; it’s based on a traditional Mexican Judas figure Kahlo kept in her own home, which was typically used in ceremonies symbolizing the defeat of evil.

As someone observing this deeply personal canvas, you’re also engaging with Kahlo’s life story. Her lifelong suffering from polio, a traumatic bus accident, and complex relationship with Diego Rivera deeply influenced her art. The bed in the painting echoes her painful experiences—it was both her refuge and her prison during long recovery periods. Her use of cultural symbols, such as retablos and calacas, invites you to explore themes of physical pain, emotional betrayal, and spiritual reckoning through a uniquely Mexican lens.

Though often grouped with European surrealists, Kahlo distanced herself from the movement. You’ll notice her art doesn’t chase dreams or subconscious imagery in the surrealist tradition. Instead, it reflects her lived reality—steeped in pain, tradition, and resilience. Her own words explain it best: “I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.” As you view her work, you’re drawn not just into a dreamscape but into a deeply personal narrative interwoven with mythology, mortality, and cultural identity.