Opinion

How an ancient Bible map quietly changed the way people saw countries and borders forever

DCM Editorial Summary: This story has been independently rewritten and summarised for DCM readers to highlight key developments relevant to the region. Original reporting by The Conversation, click this post to read the original article.

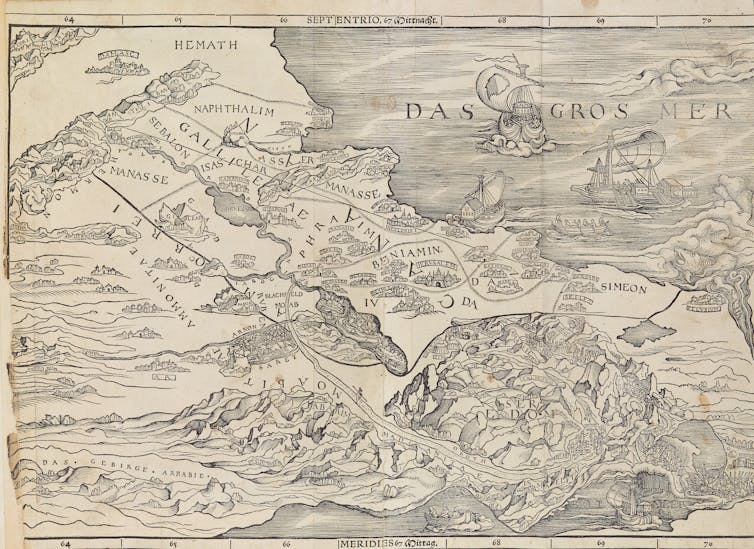

Five hundred years ago, the first Bible to include a map was published, changing how Bibles were made and perceived. You might find it surprising that this milestone, marked by Christopher Froschauer’s 1525 Old Testament, went largely unnoticed. The map, which was supposed to show the Holy Land, was actually flipped north to south, placing the Mediterranean east of Palestine instead of west. This error highlights how little Europeans at the time understood the geography of the Middle East. The map, originally created by Renaissance artist Lukas Cranach the Elder, was filled with symbolic depictions, including holy sites like Jerusalem and Bethlehem, as well as scenes from the Israelites’ journey out of Egypt.

As you explore the map, you’ll notice that it doesn’t resemble the Middle East much at all. It looks more European—with walled towns, dense trees, and oddly shaped rivers and coastlines. This artistic rendering reflects the limited knowledge of the region by those in 16th-century Europe. Earlier, the rediscovery of Ptolemy’s ancient geography had revolutionized map-making by using latitude and longitude, leading to more accurate depictions of places like France and Spain. However, efforts to modernize maps of the Holy Land fell short, often relying on outdated medieval methods that prioritized symbolic meaning over geographic precision.

In Cranach’s map, you can see a blend of ancient symbolic styles and more modern geographical features. While he included meridian lines to give the map a scientific touch, the orientation and artistic choices still lean heavily on religious storytelling. The map invites you to visually follow the Israelites’ journey, highlighting major biblical locations. It wasn’t just a navigation tool—it was a representation of Christian belief and imagination, emphasizing the spiritual over the physical reality of Palestine, then part of the Ottoman Empire.

This religious lens shaped how people like you would come to see the Holy Land: not as it truly was, but through a Christian worldview. The twelve tribal divisions shown on Cranach’s map weren’t just historical details—they carried deep symbolic weight, reinforcing the idea of Christianity inheriting God’s promises. Over time, such maps began influencing how borders were imagined and drawn in the modern world. Walls that once represented divine inheritance increasingly came to define nation-states and political territories.

Maps in Bibles eventually became standard, with four common ones chosen to symbolize both Testaments equally. These maps told stories—two of journeys and two of the Holy Land—connecting the Old and New Testaments in a visual and thematic symmetry. When you look at Bible maps today, you’re not just seeing geography; you’re witnessing a powerful blend of faith, politics, tradition, and artistic interpretation that helped shape the way you view both the ancient world and the modern one.