Opinion

Why hotter summers are bad for the UK economy

Read more on post.

When we think about the impact of climate change on the economy, images of droughts in Africa or hurricanes in the Caribbean might come to mind. But even in advanced economies such as the UK, hotter summers are being shown to carry a heavy price.

The past few summers in the UK have been among the hottest on record. In summer 2025, average temperatures across much of the country were more than 1.5°C higher than the usual seasonal average, with parts of southern England around 2°C hotter than normal. What does that mean for the economy?

The heat invites people outdoors. Beaches are packed, pub gardens overflow and families fire up the barbecue. Trade association the British Retail Consortium reported that retail sales increased by 3.1% in June compared to the same month in 2024. This was driven by a surge in sales of food, drink, and leisure products. From ice cream trips to garden makeovers and days out, sunshine typically encourages feel-good, spur-of-the-moment spending.

But warmer summers have downsides. High temperatures have a big effect on health, putting people at risk of heat stress, heat stroke and even death. Accommodation in the UK is designed to retain heat, which means that currently, 32% of homes in London and 17% of homes outside London are overheated. And the percentages of homes at risk of future overheating jump to 55% in London, and 33% in the rest of the country.

Heat also affects people while they’re at work. For those who work outside, the weather can have a serious impact on their health and wellbeing if it is not properly managed. And for indoor workers, a similar phenomenon occurs as workplaces in the UK – just like homes – are designed to retain heat.

The UK’s hotter summers have become such an issue that some unions are campaigning for a maximum temperature set by law of 30°C for non-strenuous indoor work. Currently, there is only guidance for a minimum temperature (16°C or 13°C if employees are doing physical work).

And the problems for workers can start even before they make it to work: overheated rails mean slower trains or even cancellations.

Counting the cost

Some industries are hit harder by the weather, not just through its effect on workers, but due to the heat itself. The hot summer of 2025 has made it difficult for farmers, who have seen cereal harvests shrink, grazing land dry up and animals suffer. In some areas, up to half of cereal and potato crops have been lost, with harvests arriving two to three weeks earlier than usual.

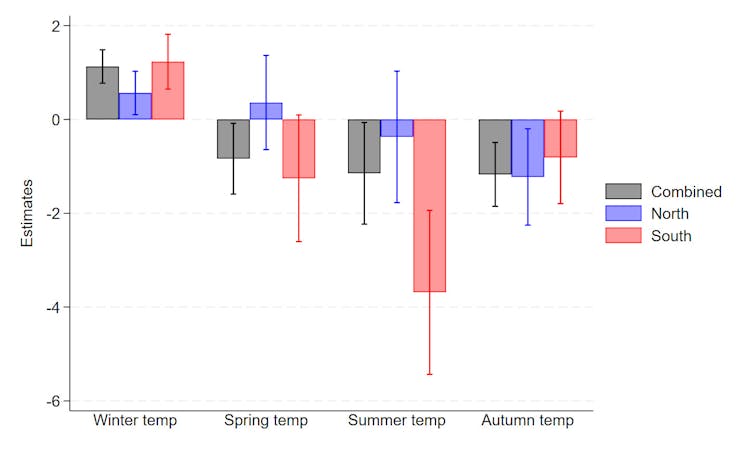

So, are hotter summers good or bad for the UK economy? Our study examined more than two decades of local economic data across the UK and matched it with seasonal temperature records. We found that a 1°C increase in summer temperatures reduces UK economic growth by about 2.4%.

Effect of 1°C rise in seasonal temperature on UK economic growth (%)

Author provided (no reuse)

In practical terms, that means that even a modest rise in average summer heat can shave billions of pounds off the economy. But why does this happen?

Hot summers disrupt work and production. Businesses may see more staff off sick due to heat stress and related illnesses. Productivity in offices, factories and farms often drops as workers struggle in higher temperatures.

Our study shows that the agricultural sector is especially vulnerable. Hot, dry summers damage crops and livestock, and since much of the UK’s general cropping and dairy farming is concentrated in the south of the country, this area bears the brunt of economic losses.

Maulana Noriandita/Shutterstock

Our findings also reveal that the impact of hot summers is not evenly spread across the country. Wealthier councils (those with an annual GDP higher than the national average income) are actually more vulnerable. The south of England, comprising the south-east (including London), the south-west, and the east of England, experiences the sharpest economic declines.

This is partly because the south is both hotter on average and home to many of the country’s farms. London alone, which generates more than half of the UK’s financial services output, emerges as a key “hotspot” of vulnerability.

We also found evidence that patterns of energy use matter. During hot summers, electricity consumption drops compared to during other seasons. While this might sound like a good thing, it signals reduced industrial activity, offices closing or shifts in working patterns that dampen economic growth.

The message from our research is clear – hot summers are not just uncomfortable, they are economically costly. Unless adaptation measures – better cooling infrastructure, workplace protections and support for climate-resilient farming – are introduced, the UK risks losing billions as heatwaves become more frequent.

Climate change cannot be dismissed as a distant challenge. Our research shows its economic fingerprints are already visible in Britain’s summer heat. Preparing for hotter summers is not just an environmental issue, it is an urgent economic priority.

Opinion

Paddy Monahan: New primary school curriculum baulks at the chance to get religion out of the classroom

Read more on post.

The new primary school curriculum may have an increased focus on Stem subjects, languages and personal wellbeing, but it is a missed opportunity to tackle the religious discrimination that is sewn into the fabric of the Irish primary education system.

Parents will continue to be frustrated as non-Catholic children remain isolated and segregated during school. Teachers will go on holding their tongues for fear of risking their careers under the vague and broad prohibition against “undermining the religious ethos” of a school under Section 37.1 of the Employment Equality Act.

Almost 90 per cent of Irish primary schools remain controlled by the Catholic Church. Although they are entirely funded by taxpayers, the patron (in Dublin that means the Archbishop) appoints the board of management, which in turn appoints the principal and teachers. Under the existing curriculum, 2½ hours per week are devoted to Catholic faith formation – almost as much as history, geography and science combined. And this timetabled “faith formation” does not include daily prayers, clerical visits and, crucially, sacramental preparation – to which endless hours are sacrificed in the months leading up to Confirmation and Holy Communion.

What changes are proposed under the new curriculum? Well, under social and environmental education children are now to learn about other religions. “About” is the key word here – children will learn about world religions from a historical and geographical perspective. This is not indoctrination and is not objectionable.

On the other hand, timetabled Catholic faith formation is to continue as always – albeit, reduced from 2½ to two hours per week for children from first class onwards; or one hour and 40 minutes for younger classes. In itself this reduction is pretty unremarkable – 20 per cent less religious discrimination for older classes is a poor achievement in a 21st-century democracy. Regardless, sacramental preparation will remain unaffected by the new curriculum. In reality, the time spent on religious faith formation will be as long as a piece of string.

Meanwhile, the Minister for Education, Helen McEntee, has offered confused messaging about the faith formation aspect of the new curriculum.

At the heart of the issue for many families is the deeply flawed “opt-out” system. The Constitution sets out at Article 44.2.4 “the right of any child to attend a school receiving public money without attending religious instruction at that school”. But in practice this means parents having to proactively contact schools to request their child not receive faith formation. Many hesitate at this point, not wishing to stigmatise their child in the classroom or mark them out as different. If they proceed their child will, in any event, remain in the classroom during faith formation, absorbing the lesson regardless while engaged in non-curricular busywork.

The situation is significantly worse in the sacramental years, when opted-out children are brought to church again and again to sit at the back and kill time while their friends prepare for the big day.

On The Last Word with Matt Cooper on Monday, McEntee was asked whether the new curriculum will give parents an effective choice as to whether their child remains in the classroom during daily religious faith formation lessons. She responded that “there is already a very clear structure set out. So if a child is attending a school where the particular patronage, for example, if it’s a Catholic patronage, but they don’t wish to be involved in that particular patronage programme, there is already very clear guidelines set out as to what that child should be doing at that time”.

This will be news to countless parents around the country who have been run ragged by schools when seeking a clear answer to the question of how they will accommodate their opted-out child. The Education (Admissions to Schools) Act 2018 was welcomed for stating that a school’s admissions policy must “provide details of the schools arrangements” where a child’s parents have “requested that the student attend the school without attending religious instruction”. However, in the intervening years, it has become clear that schools are simply refusing to supply any such written “details”.

Instead, in clear breach of the legislation, schools simply say a meeting must be arranged with the principal. For this reason, Education Equality, the organisation I represent, has repeatedly called on McEntee and her predecessors to provide guidelines for schools on “opting out”. None have ever been forthcoming. Nevertheless, the Minister claims these guidelines are in place.

However, in reality, there is no effective way to opt out of faith formation that does not lead to exclusion and discrimination. Even removing a child from the room for these periods is stigmatising – and something schools are quick to point out is beyond their resources. The obvious answer is for any religious faith formation to take place outside school hours on an opt-in basis. This upholds the rights of all and surely could not cause offence to anyone.

The new curriculum was an opportunity to disentangle religious discrimination from education once and for all. Instead, we have an Irish solution to an Irish problem. What we will have now is teachers saying “Christians believe Jesus was the son of God” in one lesson followed by “Jesus was the son of God” in the next. And if they want to keep their jobs they won’t dig any deeper than that.

Paddy Monahan is a teacher, Social Democrats councillor and policy officer with Education Equality

Opinion

Starmer should have conference in his hands – instead, power is slipping through his fingers | Frances Ryan

Read more on post.

A little over a year since Labour took office in a landslide and, with the Conservatives flatlining, by any measure, Keir Starmer should be riding into next week’s party conference as, if not quite a conquering hero, a leader in his prime. Instead, he is mired in tanking poll ratings, three scandalous exits and plots by his own MPs to oust him. If the early days of Starmer’s leadership ran with such ease that it spawned the joke he must have found a genie’s lamp, it appears his wishes have well and truly run out.

The idea that Labour’s return to power has been a crushing disappointment is now a well-worn one. From shirking on Gaza and crashing on benefit reform to trusting Peter Mandelson, so far, Starmer’s premiership is a lesson in lost potential, where if a poor decision can be made, it will be and then some.

If it has felt at times to Starmer’s supporters over the past year that he is held to account too harshly, to others, he has unforgivably thrown away not only a precious opportunity but an obligation. You did not have to believe Starmer was going to be Britain’s saviour in July last year to hope he would at least offer some respite after a decade and a half of Tory misrule. That after the public endured austerity, Brexit and Partygate, and at last rid itself of their architects, there could actually be something better around the corner.

Instead, we have been plunged into a groundhog day loop of missed chances: Starmer makes a bad call, a varying-sized chunk of the parliamentary Labour party complain, and a clique-based Downing Street operation – steered by under fire chief of staff Morgan McSweeney – dig their heels in (typically making the situation 10 times worse). Meanwhile, the reasons to elect a Labour government – say, tackling child poverty or building a humane benefits system – go largely unmet and unfulfilled. It is why the latest talk about scrapping the two-child benefit limit feels empty, as we are forced yet again to play the game where a government with a working majority of 156 pretends all of this is out of its hands.

This would be infuriating at any time but has become deeply worrying in light of the surge of Reform UK and wider nationalism. That Starmer will pledge at the Global Progress Action Summit on Friday that his government will lead the fight against the “decline and division” fomented by the far right – a move in stark contrast to the passivity of recent months – suggests he is at least partly aware of the urgent need to reset. But one speech will not compensate for an agenda that fails to make the positive case for immigration and asylum rights. The fact Labour will never be able to satisfy the staunch anti-immigration vote when Reform offers mass deportations (and the claim migrants are eating our swans) makes the chase more tragic still. On its worst days, Starmer’s government is akin to a mediocre tribute band playing cover versions to a crowd who will always prefer the original.

It is often remarked that Starmer finds himself in trouble because he favours managerialism over a vision for the country. That’s true in a way. More than a year in, it is no clearer what Starmerism is “for”, with posturing on flags and the value of work used as a substitute for any sort of narrative. But the issue is also that, far from a break from the chaos associated with the Conservatives, Starmer’s administration has been beset by avoidable errors, inaction and crisis, all on top of the broken public realm and tough finances it inherited. Or to put it another way: basing your project around “delivery, delivery, delivery” only works if you actually deliver. Most voters don’t care about a prime minister’s lack of charisma or sweeping oratory if they can get a GP appointment and pay the weekly food shop. The problem is they still can’t.

after newsletter promotion

The public might be inclined to be more patient if the early signs from Starmer were trustworthy and consistent. After all, no one can overturn 15 years of Tory decline in 15 months. But, after his first year in office, few voters would say they know who their prime minister is, and what they do see seems inauthentic. The son of a toolmaker who is a knight of the realm. The human rights barrister who acts tough on asylum seekers. Add in his chameleon behaviour on policy and early missteps, and the PM has already been defined by frequent U-turns, freezing pensioners and gifted designer glasses. That, in contrast, the genuinely good stuff – from introducing family hubs and the workers’ rights bill to fixing crumbling infrastructure – has barely registered is both deeply unfair and a mess of Starmer’s own making. If you want credit for, say, extending sick pay for workers, stop banging on about taking chronically ill people’s benefits.

And yet the really worrying thing for Starmer is not the critiques from his own side, but that many feel it is not worth trying any more. That some insiders are now plotting about how to make Andy Burnham Labour leader – a figure who is not currently even an MP – suggests the dial has been moved. Critics are no longer at the stage of vainly hoping Starmer will be someone else. That there is a principled and politically savvy leader lurking there, who – with enough nudges – will make the right choices and listen to a diversity of voices, despite all evidence to the contrary. They know who Starmer is and the question now is: is that going to be enough? And if not, what comes next? That’s a remarkable state of affairs for a premiership with almost four years left on the clock, and a sign of just how horribly things have gone.

Starmer’s trailed rebuff to the far right and investment in deprived areas may be the beginnings of a wider fightback. But if he wishes to turn things around, he must first grasp it is not only his career or even the Labour party at stake – it is the country. Because if Starmer does not change tack, he will not just have failed to heal the damage the Conservatives inflicted – he will have opened the door wide for a Reform government. As things stand, it is already ajar.

-

Frances Ryan is a Guardian columnist

Opinion

Justine McCarthy: If Northerners had a vote, Catherine Connolly would be our next president

Read more on post.

Catherine Connolly’s presidential election campaign would be a stroll to the park if Ireland honoured all its citizens’ rights. Instead, the Independent candidate is being accused of lip service by two parties that have ensured the exclusion of hundreds of thousands of potential voters from choosing their head of state.

Irish citizens living in Northern Ireland are allowed no say in an election that is being billed as crucial to their future constitutional status. Sinn Féin insists the next president must “champion a united Ireland”. Fine Gael says its candidate, Heather Humphreys, as a Presbyterian from a Border county, would symbolically unite the island. Fianna Fáil presents its candidate, Jim Gavin, as being Border-blind due to his involvement with the all-island GAA. Yet those living in the North’s six counties are silenced in the election. Their continuing exclusion reduces them to nominal citizens.

Addressing his party’s annual conference last weekend, DUP leader Gavin Robinson rebuked the Republic for what he called its “institutional intolerance of Protestant culture and heritage” but the southern State’s starker prejudice is against its own citizens in the North. Under the 1956 Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act, affirmed by the 1998 Belfast Agreement, people in Northern Ireland are entitled to choose to be citizens of Ireland. As such, the Irish President is their president. Ever since Mary Robinson’s election to the Áras in 1990, the office’s holders have striven to represent them with their presence and their utterances. But across the Liffey in Government Buildings the realpolitik means that extending voting rights to Northern citizens would be electoral hara-kiri, virtually handing Sinn Féin the presidency on a plate.

Sinn Féin, Connolly’s major backer, is the biggest party in Northern Ireland and the biggest all-island one. It got 250,388 first-preference votes in the most recent Assembly elections in May 2022. On a crude calculation, if you add the SDLP’s 78,237, Aontú’s 12,777 and, conservatively, a third of both the Alliance Party’s 116,681 votes and People Before Profit’s 9,798, you get more than 380,000 potential active ethnonationalist voters in the North in 2022. While some – particularly SDLP voters – might back Fianna Fáil, they would be a proportion of a larger turnout than the 63.6 per cent three years ago, attracted to polling stations by the unprecedented opportunity to cast their preference for president. Northerners have a vested interest in an election portrayed as seminal for the abolition of partition. Unlike voters in the rest of the island, the constitutional status is a priority issue with some voters in the North. Respondents there ranked it third, behind cost of living and healthcare, in a survey conducted last year by researchers at the University of Liverpool.

Denying legions of potential voters the right to choose their first citizen is an extreme exercise in gerrymandering. This continuing snub to our compatriots shrinks the winner’s mandate. Outsiders might presume it to be an Irish joke that Rostrevor resident Mary McAleese could not cast a vote for herself when she won the 1997 election. Once the Irish Government-funded Narrow Water Bridge over Carlingford Lough is completed, the journey from Rostrevor to Omeath in the Republic will be less than five miles.

The delaying by successive governments in enfranchising Irish citizens in Antrim, Armagh, Derry, Down, Fermanagh and Tyrone evokes Ronnie Corbett.

He made a plea to his mother that he wanted to marry and pass on his genes and she replied that she had given them to Oxfam – such was her determination to keep her 42-year-old son under her roof as a half-fledged adult. In 2017, during the Brexit negotiations, then taoiseach Leo Varadkar promised that “no Irish government will ever again leave Northern nationalists and Northern Ireland behind”. Yet four years earlier, a constitutional convention had recommended that a referendum be held to extend presidential voting rights. An Oireachtas Bill providing for such a referendum in 2019 turned out to be fiction. As an anonymous wag once scribbled on Samuel Beckett’s headstone in Montparnasse Cemetery, “we’re still waiting”.

[ What did voters say about governing a united Ireland?Opens in new window ]

Belfast woman Emma de Souza was hailed as something of a national hero when she successfully sued the British government to establish her right to be considered Irish from birth. Yet, unless she has since registered to vote in the Republic as a resident, she is prohibited from participating in picking her president. A commitment to extend voting rights in presidential elections was contained in the 2020 programme for government but it has been dropped from the current one. In another country, this would be at least as topical during the election campaign as is the nominations requirement to be a contestant, about which there has been much olagóning. The silence is indicative of a news media that, by and large, treats Sinn Féin with deep suspicion. While it may be an understandable attitude among those in the South who remember the horrors of the Troubles, it is indefensible to refuse Irish citizens in the North who lived through it their right to vote for their president. Parity of esteem is the foundation principle of the Belfast Agreement but, when it comes to electing a president, there is no equal regard for Irish citizens living on this island.

The political establishment’s double standard is so ingrained it seems unaware of it when accusing Connolly of being a latecomer to the ideal of Irish unification. During a Dáil debate on Brexit in 2020, she said: “If anything comes out of [it], I hope it will be a reunited Ireland by peaceful means.” That and other of her comments on the topic are too awkward for her critics to mention while they use Northern Ireland as a weapon to damage her campaign. Ditto her comment about Hamas being part of Gaza’s fabric and the right of Palestinians to self-determination. Unpalatable perhaps, but true. Had the same truth not been acknowledged about the IRA, there would not have been a peace process. There would be no Belfast Agreement.

While these political grenades get flung around in the Republic, Irish citizens who lived with the reality in Northern Ireland are forced to sit silently and watch as mere spectators. It is wrong.

-

Culture3 days ago

Taylor Swift’s new cinema outing generates more than €12million in just 24 hours

-

Politics3 days ago

European Parliament snubs Orbán with vote to shield Italian MEP from Hungarian arrest

-

Health4 days ago

EU renews support for WHO’s Universal Health Coverage Partnership

-

Culture3 weeks ago

Life, loss, fame & family – the IFI Documentary Festival in focus

-

Environment6 days ago

Key oceans treaty crosses threshold to come into force

-

Culture3 days ago

Twilight at 20: the many afterlives of Stephenie Meyer’s vampires

-

Culture2 months ago

Fatal, flashy and indecent – the movies of Adrian Lyne revisited

-

Culture1 week ago

Farewell, Sundance – how Robert Redford changed cinema forever