Opinion

Why some people are purposefully having their legs broken by cosmetic surgeons

Read more on post.

Would you willingly have your legs broken, the bone stretched apart millimetre by millimetre and then spend months in recovery – all to be a few centimetres taller?

This the promise of limb-lengthening surgery. A procedure once reserved for correcting severe orthopaedic problems, it has now become a cosmetic trend. While it might sound like a quick fix for those hoping to make themselves taller, the procedure is far from simple. Bones, muscles, nerves and joint all pay a heavy price – and the risks often outweigh the rewards.

Limb lengthening is not new. The procedure was pioneered in the 1950s by Soviet orthopaedic surgeon Gavriil Ilizarov, who developed a system to treat badly healed fractures and congenital limb deformities. His technique revolutionised reconstructive orthopaedics and remains the foundation of current practice today.

While the number of people undergoing cosmetic limb-lengthening surgery each year still remains relatively small, the procedure is growing in popularity. Specialist clinics in the US, Europe, India and South Korea report increasing demand – with procedures costing tens of thousands of pounds.

Reports suggest that in some private clinics, cosmetic cases of limb-lengthening surgery now outnumber medically necessary ones. This reflects a cultural shift, where people are willing to undergo a demanding, high-risk medical procedure to meet social ideals about height.

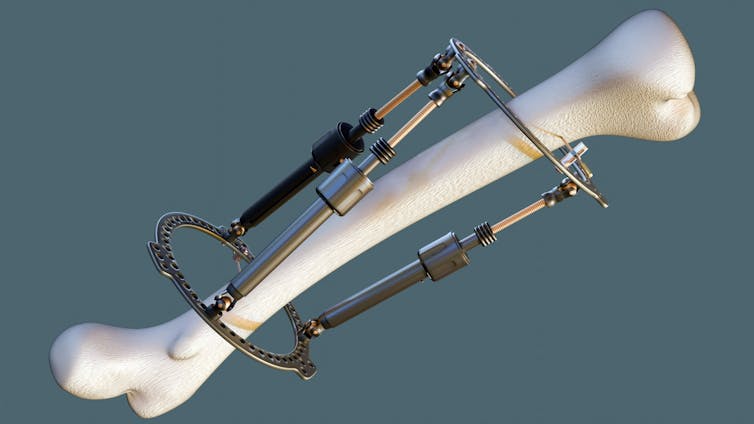

Surgeons begin by cutting through a bone – usually the femur (thigh bone) or tibia (shin bone). To ensure the existing bone stays healthy and that new bone can grow, surgeons are careful to leave intact its blood supply and periosteum (the soft issue that covers the bone).

Traditionally, the cut bone segments were then connected to a bulky external frame which was adjusted daily to pull the two ends apart. But more recently, some procedures have adopted telescopic rods placed inside of the bone itself.

These devices can be lengthened gradually using magnetic controls from outside the body – sparing patients the stigma of an external frame and reducing the risk of infection. However, they’re not suitable for all patients – especially children – and are considerably more expensive than external systems.

Love Employee/ Shutterstock

Regardless of whether the device sits outside or within the bone, the process is the same. After a short healing period, the device is adjusted to separate the cut ends very gradually, usually by about one millimetre per day. This slow separation encourages the body to fill the gap with new bone – a process called osteogenesis. Meanwhile, the muscles, tendons, blood vessels, skin and nerves stretch to accommodate the change.

Over weeks and months this can add up to a gain of five to eight centimetres in height from a single procedure – the limit most surgeons consider safe. Some patients undergo operations on both the femur and tibia, aiming to gain as much as 12–15 centimetres in total. However, complication rates rise sharply with each centimetre of additional growth. Complications include joint stiffness, nerve irritation, delayed bone healing, infection and chronic pain.

Intense pain

The underlying challenge of limb-lengthening surgery is the same: the body must constantly repair a bone that is being pulled apart.

When a bone breaks, a blood clot rapidly forms around the fracture. Bone cells (ostoblasts) create a callus (soft cartilage) that stabilises the break. Over weeks, osteoblasts replace this cartilage with new bone that gradually remodels to restore strength and shape.

In limb-lengthening surgeries, however, the fracture is continuously pulled apart. This means the body’s repair process is constantly interrupted and redirected, generating a column of delicate new bone where hardening is delayed.

The process is intensely painful. Patients often require strong painkillers. Physiotherapy is also essential to maintain movement. Yet, even when the surgery succeeds, people may still be left with weakness, altered gait or chronic discomfort.

There’s also the psychological burden that comes alongside the procedure. Recovery can take a year or more – much of it spent with restricted mobility. Some patients report depression or regret, particularly if the modest gain in height does not deliver the hoped-for improvement in confidence.

Muscles and tendons are also forced to lengthen beyond their natural capacity, which can lead to stiffness. Nerves are especially vulnerable. Unlike bone, they cannot regenerate across long distances. Healthy nerves can stretch by perhaps 6–8% of their resting length – but beyond this, the fibres begin to suffer injury and become impaired.

Patients often experience tingling, numbness or burning pain during lengthening. In severe cases, nerve damage may be permanent. Joints, immobilised for months, are at risk of stiffening or developing arthritis because of changes to how force and weight are distributed.

The rise of cosmetic limb-lengthening illustrates a broader trend in aesthetic surgery – where increasingly invasive procedures are offered to people without medical need. In theory, almost anyone could gain a few centimetres of height. But in practice, it means months of broken bones, fragile new tissue, exhausting physiotherapy and the constant risk of complications.

For those with medical need, the benefits can be life-changing. But for those seeking only to add a little height, the question remains whether enduring months of pain and uncertainty is really worth it.

Opinion

The Irish Times view on Donald Trump’s autism warning: the war on science must be resisted

Read more on post.

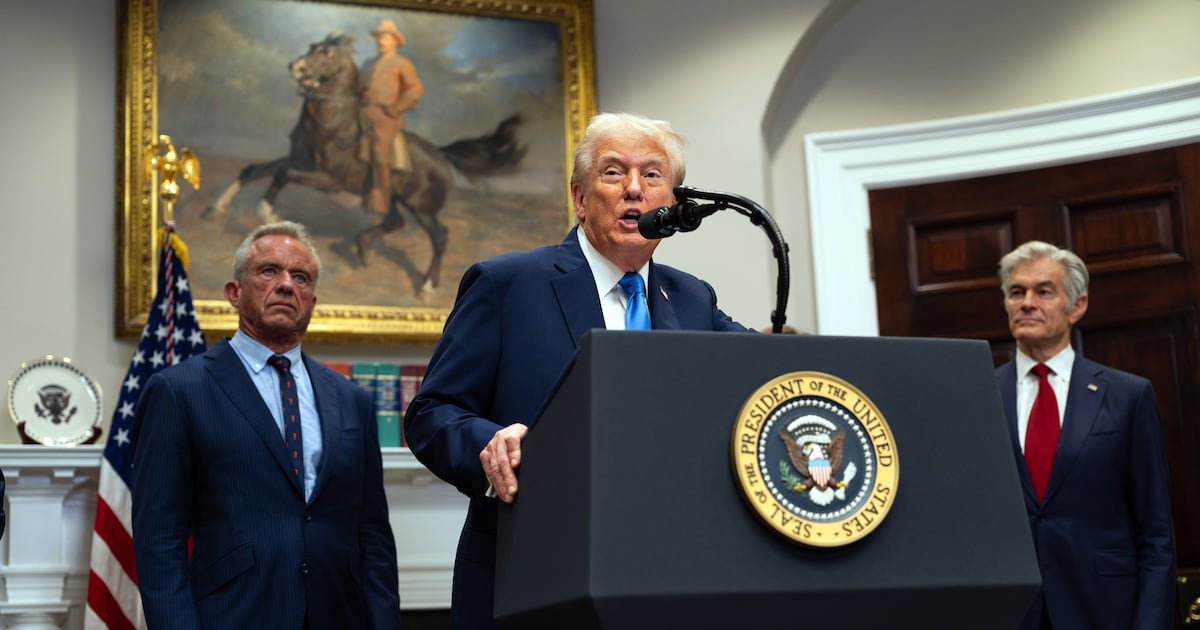

Donald Trump’s performance at the White House this week, asserting that a common painkiller is driving a surge in autism, was a particularly egregious piece of political malpractice, even for him. His sweeping claims about acetaminophen were not even reflected in his administration’s own accompanying documentation, which spoke in qualified terms about possible associations and the need for further study.

Outside the US, acetaminophen is sold under its international name, paracetamol, and is generally the first-choice painkiller advised for use during pregnancy following decades of use and large studies showing it is safe at recommended doses.

Citing extensive research, the World Health Organisation said there is no consistent association between acetaminophen use in pregnancy and autism; it advised women to follow the guidance of their doctors and pointedly also reminded the public that vaccines do not cause autism, contrary to claims made by US Health and Human Services secretary Robert F Kennedy jnr.

Research on acetaminophen in pregnancy has produced mixed findings. Some observational studies report associations with later neurodevelopmental diagnoses; others that compare siblings or control better for confounding factors find the association falls away. In clinical terms, the advice given to pregnant women remains unchanged: use necessary medicines judiciously and at the lowest effective dose.

Ireland is governed by EU standards on public health and communication. Those frameworks require strong, reproducible evidence before practice is revised. But unsupported theories like the ones now coming out of the White House do not stop at borders. Similar narratives circulate widely on this side of the Atlantic, often folded into older, discredited vaccine myths. But the record is clear: large studies across many countries have found no causal link.

As for the larger question of why recorded autism rates have risen, the best explanation is multi-layered: diagnostic criteria have expanded; awareness among clinicians and parents has grown; screening has become more routine; social acceptance has encouraged families to seek assessment. These factors explain much of the steep increase in the US and Europe, including Ireland. Specialists also point to a complex interplay of genetic predisposition and broader environmental influences as possible contributors. But that is a research frontier, not a verdict on any single over-the-counter medicine.

When an American president recasts preliminary findings as a simplistic story of cause and effect, public trust inevitably erodes. It is deeply worrying that the forces of irrationality are now in positions of such influence from which to prosecute their war on science.

Opinion

The Irish Times view on the Starmer question: Labour should be careful

Read more on post.

The pressure is mounting on Keir Starmer ahead of the UK Labour party conference starting this weekend. Fifteen months after the party’s landslide general election victory, there are question marks over his continued premiership. Starmer’s vulnerability is partly self-inflicted but it also underlines the challenges he faces.

The UK has registered anaemic growth levels for well over a decade, on the back of a long line of policy mistakes. Prior to the 2024 election, Labour pledged no income tax rises, which has meant a raft of new business taxes, further depressing growth. It also promised 1.5 million new homes by 2029, but construction activity has fallen to its lowest level since the Covid pandemic.

Starmer has had an unfortunate mix of bad luck (losing deputy prime minister Angela Rayner) and bad judgment (the attempt to cut the winter fuel allowance). Labour languishes at 20 per cent in opinion polls while Nigel Farage’s Reform is riding a wave of anti-migrant and anti-establishment sentiment.

To the left, Labour is under threat from the Liberal Democrats and the Greens. It remains to be seen what impact former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn’s new party will have.

Last month, Starmer reshuffled his cabinet in an effort to inject a new sense of purpose. So far there is no tangible signs this is paying dividends.

Just days before the conference starts, Andy Burnham, the popular mayor of Manchester, has launched a scathing attack on Starmer, calling his style of leadership divisive and saying he lacks a credible plan.

The comments are widely seen as an opening salvo in a leadership challenge.

There is no doubt Starmer has made mistakes. But the reality is that Brexit inflicted deep economic wound there are no easy solutions.

The Conservatives elected five different prime ministers in nine years in the mistaken belief that changing personalities would change outcomes. That led to instability and stasis. Labour would do well to remember such a recent lesson.

Opinion

Alison Healy: Renewed push to honour Finnish sailor who fought in the Easter Rising

Read more on post.

It may be 109 years since the Easter Rising, but the State would like to award one more 1916 medal. It’s for a man from Finland who apparently had no connection with Irish republicans until he turned up at the GPO in April 1916.

At least four different versions of his name turned up in various accounts of the Rising and his nationality veered from Russian to Polish to Norwegian, depending on who was interviewed. But thanks to research by Dr Andrew Newby, historian at the University of Galway, we now know that his name was Antti Juho Mäkipaltio.

He was a sailor who found himself in Dublin with his Swedish colleague that fateful spring. The Swedish man’s name has been lost in the mists of time, but perhaps that will also be revealed one day.

Captain Liam Tannam of the Irish Volunteers gave an account of the Nordic men’s arrival in his witness statement held by the Bureau of Military History. On Easter Monday afternoon in the GPO, he was called to the window and saw “two obviously foreign looking men”. The Swede said they wanted to help the Irish rebels and explained that Mäkipaltio had no English.

The bemused Tannam asked why a Finn and a Swede would want to fight the British in Ireland. “Finland, a small country, Russia eat her up… Sweden, another small country, Russia eat her up too. Russia with the British, therefore, we against,” his statement recalled.

When asked about their experience with weapons, the Swede said he had used a rifle before but Mäkipaltio only had experience shooting fowl. He had not exaggerated about his friend’s lack of skills. Mäkipaltio was handed a shotgun and at one point, he let his gun hit the floor. It discharged and released a shower of plaster on the men’s heads.

Irish Volunteer Charles Donnelly’s statement said that when James Connolly heard about it, he declared: “The man who fires a shot like that will himself be shot.”

To avoid any more casualties, Joseph Plunkett asked them to fill fruit tins with explosives. When the surrender came, both men were captured but the Swedish man was quickly released.

Mäkipaltio, on the other hand, found himself in Kilmainham Gaol. Although he had no English, Tannam claimed he was saying the rosary in Irish before he left. He was sent to Knutsford Prison in Cheshire with his fellow rebels on May 2nd before being finally freed several weeks later.

Dr Newby’s research found that although Finnish media reported on various 1916 anniversaries, there was no mention of Mäkipaltio until recently. When the Finnish president Tarja Halonen visited Ireland in 2007, she referred to claims that a Finn had taken part in the Rising but said she didn’t know if it was a myth.

When Dr Newby began working on his book Éire na Rúise (The Ireland of Russia), about Finland and Ireland, he knew he had to establish the identity of the Finnish rebel. Jimmy Wren’s book, The GPO Garrison Easter Week 1916, was most useful as it said he had gone to the US after the Rising. Dr Newby discovered a newspaper report of a talk given by Mäkipaltio in New York in 1917.

He talked about the hunger in prison and of seeing rebels being beaten in the prison yard. He told the audience he had walked to Northern Ireland after being returned to Dublin. He sailed to the US from there, arriving in Philadelphia on June 24th, 1916.

His experience in the GPO must have stood him in good stead as he became a sergeant in the US army. After the first World War, he lived in Ohio and Illinois before settling in Michigan and working as a tool and die maker. He died in 1951.

[ The GPO is not ‘sacred ground’. It’s so much more than thatOpens in new window ]

Dr Newby tracked down Mäkipaltio’s step granddaughter who said his descendants knew about the Irish adventure. Family lore suggested that rather than deliberately travelling to take up arms against British forces, the duo had missed their boat’s departure from Dublin and took the opportunity for adventure.

When the Rising centenary was commemorated in 2016, Dr Newby said there was a suggestion that Mäkipaltio would be posthumously awarded a 1916 medal. I asked the Department of Defence if that had ever happened and a spokesman confirmed that a decision had been made to award the medal.

However, officials had been unable to reach his relatives. “The Department would be happy to hear from the family and ensure that the 1916 medal can be presented to his next-of-kin,” he said.

Efforts are now being made by Dr Newby to renew his contact with the family. Perhaps, by the time the 110th anniversary rolls around, Antti Juho Mäkipaltio will finally be recognised for his small role in the Easter Rising.

-

Culture3 days ago

Taylor Swift’s new cinema outing generates more than €12million in just 24 hours

-

Politics3 days ago

European Parliament snubs Orbán with vote to shield Italian MEP from Hungarian arrest

-

Health3 days ago

EU renews support for WHO’s Universal Health Coverage Partnership

-

Culture2 weeks ago

Life, loss, fame & family – the IFI Documentary Festival in focus

-

Culture2 months ago

Fatal, flashy and indecent – the movies of Adrian Lyne revisited

-

Culture3 days ago

Twilight at 20: the many afterlives of Stephenie Meyer’s vampires

-

Environment6 days ago

Key oceans treaty crosses threshold to come into force

-

Culture1 week ago

Farewell, Sundance – how Robert Redford changed cinema forever