Other News

‘It’s the human response’: Dublin barrister on why she’s sailing with the Gaza aid flotilla

Other News

‘Patronising’ to suggest older people won’t migrate to digital boarding passes – O’Leary

Other News

Dublin Fire Brigade attend multiple vehicle N2 collision – live updates

Read more on post.

A busy beginning to Thursday afternoon on the capital’s roads and we’ll be bringing you the latest alongside LiveDrive on Dublin City 103.2FM.

Dublin Fire Brigade are the scene of a multiple vehicle collision on the N2. It includes four vehicles and it’s at the Windsor Motormall on the route.

Heavy delays are reported in the area. There are also delays for vehicles coming off the M50 and onto the N2.

The M50 is getting quite busy already on the northbound side. There are delays from Firhouse past the Red Cow and then just after Lucan up to Ballymun. Southbound it’s slowest coming from the M1 and then in spots up to Lucan.

We’ll have all the latest traffic updates in our live blog below. If you have an update for us, drop an email to news@dublinlive.ie.

Join our Dublin Live breaking news service on WhatsApp. Click this link to receive your daily dose of Dublin Live content. We also treat our community members to special offers, promotions, and adverts from us and our partners. If you don’t like our community, you can check out any time you like. If you’re curious, you can read our Privacy Notice.

For all the latest news from Dublin and surrounding areas visit our homepage.

Other News

Geography and politics stand in the way of an independent Palestinian state

There has been a recent rush of countries to formally recognise the state of Palestine. Affirming Palestinian sovereignty marks a historic diplomatic milestone, yet the exact layout of its territory, a central requirement under international law, remains fiercely contested from every hilltop in the West Bank to the ruins of Gaza.

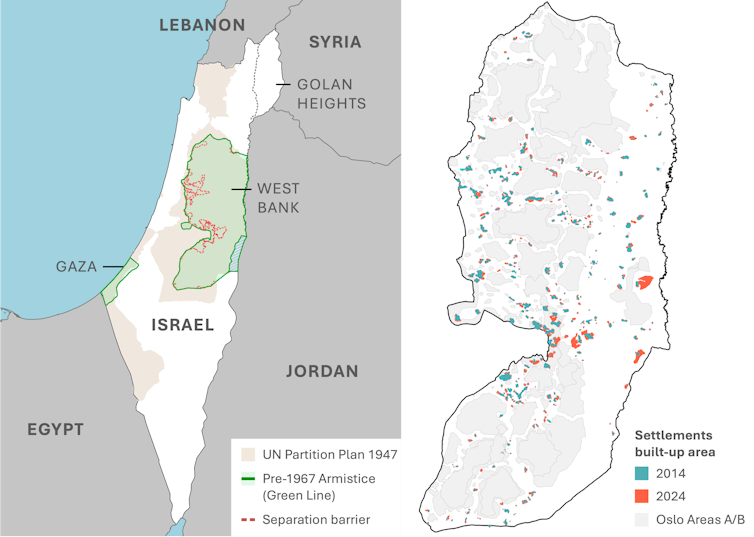

To grasp what this moment means, we need to trace how borders have evolved – or dissolved – over Palestine’s tumultuous political history. The 1947 UN partition plan had envisioned two semi-contiguous territories for Jewish and Arab states, with Jerusalem as an international city.

But that vision quickly collapsed into the war that led to the establishment of Israel in 1948. Palestinians found themselves confined to the West Bank and Gaza Strip as fully separated territories, demarcated by the “green line” and placed under Jordanian and Egyptian control.

These initial contours remain the internationally recognised basis for Palestinian statehood until today – and are referred to as the “pre-1967 borders”. That year, the six-day war saw Israel effectively tripling its territory. It occupied all of the West Bank and Gaza Strip and annexed East Jerusalem.

Israeli settlements immediately began fragmenting Palestine’s geography, especially in the West Bank. These settlements are illegal under international law, and in many cases lacked even the government’s authorisation.

Yet they faced limited government pushback – and were often directly supported by Israeli authorities. The Oslo accords later carved the territory into Areas A, B, and C with varying degrees of Palestinian governance.

Following suicide bombings during the second intifada (2000-05), Israel built a separation barrier cutting deep inside the 1967 borders. Six decades on, the West bank resembles a fragmented archipelago more than a cohesive state territory.

Mallock & Krekel (2025)., Author provided (no reuse)

Building insecurity

In a recent study, my colleagues and I used satellite imagery to show, for the first time, what exactly this does to the West Bank. We tracked all 360 settlements and outposts that existed in 2014 across the following decade.

During this time alone, the average settlement expanded by two-thirds in size. Collectively, they now occupy 151 sq km of built-up area – compared to 88 sq km ten years ago – a 72% increase. Adding to this are hundreds of new settlements, especially with a wave of approvals following October 7 2023.

Each of these settlements comes with extensive Israeli military presence and infrastructure. This has created a complicated system of roads and checkpoints that typically exclude Palestinians, severely restricting movement and economic activity.

What’s worse, violent attacks and harassment by extremist settlers are well documented in some locations. To say that building an independent state under these conditions is challenging would be a massive understatement.

A recently approved development project on the West Bank exemplifies this. On paper, the E1 project it will be yet another settlement. But if constructed, E1 – short for “East One” – will choke off the main road running north to south outside Jerusalem, effectively cutting the West Bank in half.

Israel’s far-right finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, celebrated the move as “erasing” the idea of a Palestinian state while bolstering national security – the government’s official justification for settlement expansion.

Read more:

Israel’s plan for massive new West Bank settlement would make a Palestinian state impossible

In reality, the settlements have the exact opposite effect. Our research, involving four months of fieldwork and surveying over 8,000 Palestinians, found an alarming dynamic. Living within a few kilometres of settlements almost doubled the likelihood of engagement in high-risk and violent action (more than 82%), while moderate protest dropped by 30-36%. Similarly, support collapsed for diplomatic initiatives, and surged for violent attacks.

Critically, this isn’t simply a reaction to settler violence. Beyond the effects of such exposure, settlement presence alone intensified collective moral outrage, a cognitive state known to drive violent conflict.

Studies demonstrate how this state primes people to think in terms of threat and punishment rather than the risks of taking action – particularly dangerous in the West Bank. And this factor is likely to persist: the settler community today counts upwards of half a million people, many of them armed, violence prone, and radically opposed to leaving.

What this implies for Israeli-Palestinian relations is that, as settlements expand, so will political violence and retaliation, fuelling further cycles of conflict. The recent attack in Jerusalem, in which Palestinian gunmen shot six people just weeks after E1’s approval, tragically shows this reality already.

Looking for leaders

Any viable Palestinian state must include a vision for Gaza’s reconstruction and integration once the horrific suffering and famine caused by Israel’s brutal attacks ends. Yet as I’ve reported based on data collected in January, Gaza’s largest political constituency (32%) now consists of those who feel represented by nobody.

Hamas is militarily decimated and has lost almost all remaining support among the public. The UK and other countries have also proscribed the terrorist group. Yet no viable alternative has emerged to represent Gazans’ interests.

EPA/Tolga Akmen

Over in the West Bank, a Palestinian Authority (PA) dominated by elderly men offers little better. Three decades since its establishment as part of the Oslo peace process, it is widely seen as illegitimate, corrupt and incapable, as polls consistently show.

The most realistic governance scenario involves a restructured PA administering both territories. It’s likely this will still be dominated by Fatah but with fundamentally reformed structures and leaders.

If elections were held today, the 89-year-old president, Mahmoud Abbas, would almost certainly lose. One candidate with more prospects is the imprisoned Marwan Barghouti, complicating succession planning.

Whoever eventually leads a unified Palestine will inherit decades of failed self-governance, deep public scepticism, and Israel undoubtedly attempting to intervene in this process.

Making recognition matter

Despite massive challenges, building a functioning Palestinian state is not impossible. So recognition can be more than a symbolic act. Already, it’s reshaping in tangible ways how major powers engage with Palestinian representatives while applying meaningful pressure on Israel’s leaders.

But as nations line up to recognise Palestine, they must confront what they’re actually recognising. Given the vicious cycles of settlement expansion and violence that our research shows, recognition risks becoming an empty gesture unless this issue is addressed diplomatically head on. Without creating genuine conditions for statehood that uphold the interests of all parties, neither goal will be achieved.

The choice is no longer between one-state and two-state solutions. It’s between recognising borders that have long been rendered meaningless – or committing to build something viable. Both the future of Palestinian statehood and Israeli security may depend on that choice.

-

Culture2 days ago

Taylor Swift’s new cinema outing generates more than €12million in just 24 hours

-

Environment1 week ago

Chimps drinking a lager a day in ripe fruit, study finds

-

Politics2 days ago

European Parliament snubs Orbán with vote to shield Italian MEP from Hungarian arrest

-

Culture2 weeks ago

Life, loss, fame & family – the IFI Documentary Festival in focus

-

Health3 days ago

EU renews support for WHO’s Universal Health Coverage Partnership

-

Culture2 days ago

Twilight at 20: the many afterlives of Stephenie Meyer’s vampires

-

Environment6 days ago

Key oceans treaty crosses threshold to come into force

-

Culture2 months ago

Fatal, flashy and indecent – the movies of Adrian Lyne revisited